By Hal Parkinson

Who creates a book? Is it the author, who writes the story that fills a book’s pages? Or the illustrator, who interprets that story as visual art? Perhaps it’s the publisher, who oversees the book’s physical creation, and ensures that it can be bought by readers. Each of these answers is correct on its own but fails to capture the whole of what goes into creating a single book. In reality, they’re hugely collaborative projects, made by the careful teamwork of authors, illustrators, editors, graphic designers, printers, and publishers, among countless others whose names may not be emblazoned on the front cover of a novel.

The Lilly Library’s Capra Press mss. consists of the correspondence, notes, drafts, book design materials, and printing records of Noel Young’s publishing house, Capra Press, founded in 1969. It contains over fifty years of documents featuring the works-in-progress of authors including Charles Bukowski, Ray Bradbury, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Henry Miller–authors whose words I’ve read throughout my life, but rarely questioned how they moved from the author’s pen to the books stacked on my bedside table. In processing this collection, I was given a glimpse into the intimate relationships between each of a book’s creators, and how their collaboration influences the final products readers find in their hands.

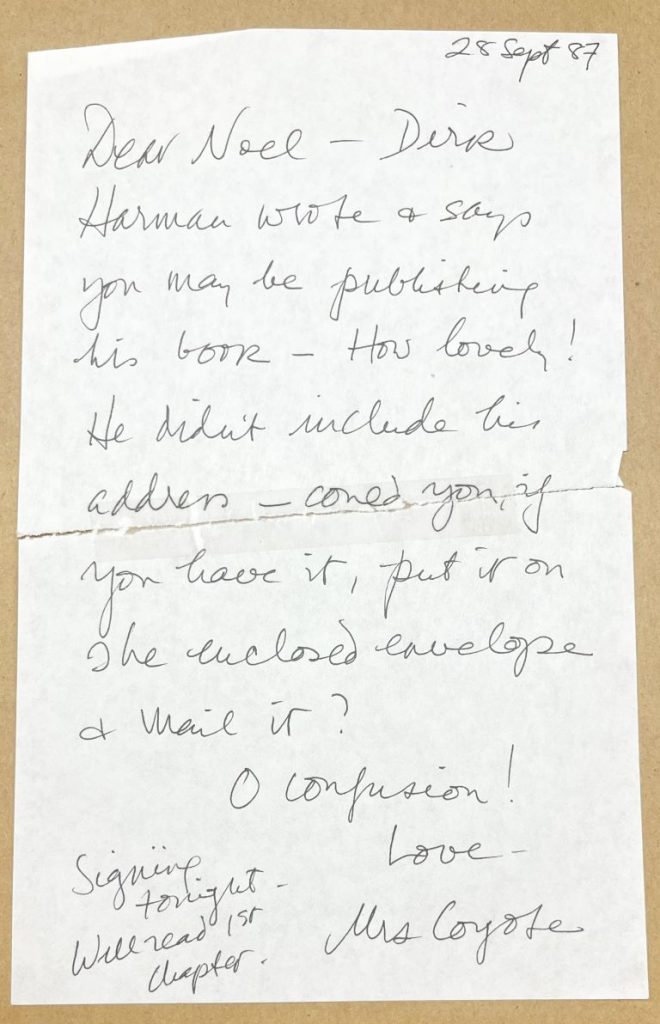

When sifting through various writers’ pieces of correspondence with Capra Press, I didn’t expect to gain a totally new perspective of their personalities. These were business letters, composed to work out deals and compromises in the publishing process, so I assumed they would be straightforward and matter-of-fact. Instead, these letters revealed how deep the relationship between author and publisher ran, and how closely the two worked together to ensure that a book fit each other’s vision. For example, Charles Bukowski’s letters are sullen with a dark sense of humor. He laments how hard it was for him to find the motivation to write–but also how intensely he felt the need to put words on a page. His letters are accompanied by numerous ballpoint pen sketches of a man writing, driving, and smoking, as though he needed to illustrate his day-to-day process. Ursula K. Le Guin, on the other hand, sounds sunny in each of her notes, scribbled on the back of postcards, hotel notepad pages, and napkins. She seemed to be always on the move, and often signed with a playful pseudonym or simply a smiley face in place of her name.

This correspondence records more than decision-making between author and publisher; it records the long running relationships that these creators kept, and shows how those relationships shaped the authors’ works. Similarly, the process of illustrating a book required a constant back-and-forth between illustrator, author, and publisher.

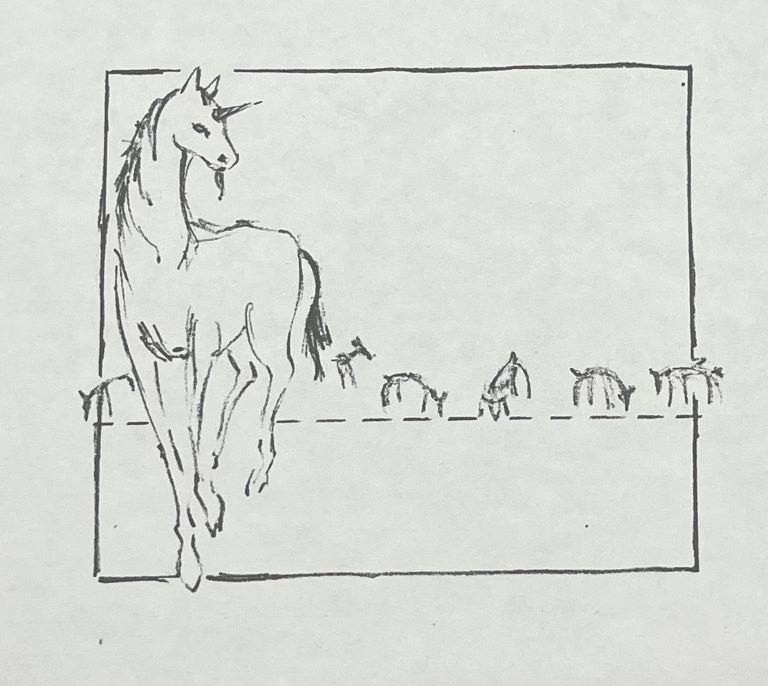

When illustrating Le Guin’s Buffalo Gals and Other Animal Presences, artist Margaret Chodos-Irvine stayed in close contact with both Le Guin and Noel Young in order to ensure that she accurately captured the right “feeling” for each of the chapbook’s short stories, while still maintaining a cohesive style throughout the book. Her early concept drawings are loose and fluid, giving her illustrated animals a strong sense of movement, as well as an air of mysterious otherness.

In a 1987 letter, she wrote that she faced a particular challenge when trying to illustrate a unicorn, as she didn’t want it to appear too childish, and therefore unappealing, to the book’s adult audience. She decided to incorporate design elements from medieval depictions of unicorns, making the creature more deer- or goat-like, as opposed to modern interpretations that resemble a white horse–or a “horsey-with-a-horn” in Chodos-Irvine’s own words.

In processing the Capra Press mss., I was given a rare look into the countless, carefully-made decisions that comprise the making of a single book. These works are not made by a single creator, but are cobbled together over months–or years–of collaboration between artists, writers, and publishers, and a look at that intricate process can transform how we see works that feel familiar.

Hal Parkinson recently completed his master’s degree in Library Science at IU in May 2023.

Leave a Reply