Ed Finegan and I have just submitted the Cambridge Handbook of the Dictionary to Cambridge University Press. If you’re a dictionary person, you’ll find it a richly informative work, thirty-one chapters about everything to do with dictionaries. The final chapter, by Gilles-Maurice de Schryver, on “The Future of the Dictionary,” reminds us of the “Bible status” of the dictionary. The Bible lays down theology and spiritual law; dictionaries lay down lexical laws, or so many of their users assume. One might guess, then, that some families had family dictionaries as well as family Bibles. Madeline owned at least one such dictionary.

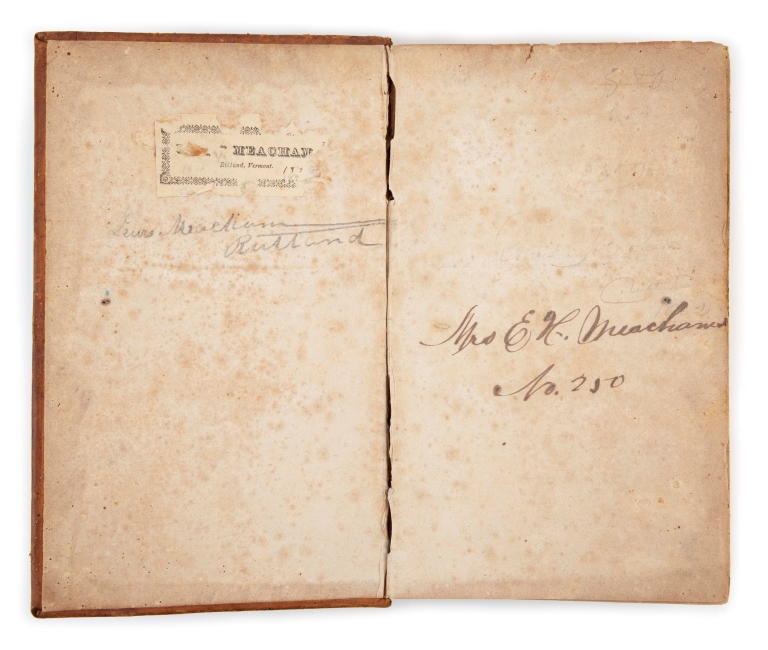

The Meachams of Rutland, Vermont, owned a copy of John Walker’s A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary and Expositor of the English Language, first published in England in 1791. It was immensely popular and, in a single volume, affordable and easy to handle. The Meachams’ copy was published in 1823 by Collins and Hannay of New York. A torn bookplate reads “Meacham” and “Rutland Vermont,” with a penned number, “18 (7),” which looks like a shelf mark — the book was shelved seventh from the left on the eighteenth shelf, wherever that was. In pencil below the plate, we read “Lewis Meacham Rutland.” On the facing cover-page, there’s a penciled “David Meacham Rutland 1832,” or is it “1882”? Then, there’s “Mrs. E. H. Meacham No. 250,” in pen.

What if the plate announced ownership of James Meacham (1810–1856), a professor at Middlebury College who served three terms in the United States House of Representatives? The Honorable James Meacham had a son named Lewis Henry Meacham, who was a big deal in baseball history and died young, without children. Lewis’ half-brother was Elias B. Meacham, and I suppose he could have had a son, Elias Henry Meacham, who married someone who became Mrs. E. H. Meacham. This is all speculation, of course. Rutland County had a surfeit of Meachams, and I may have the wrong family or the wrong interrelations among branches and generations of James Meacham’s extended family, but strangers with the name Meacham didn’t write their names into the Meachams’ dictionary — the Meacham dictionary was a family dictionary. What the dictionary meant to any of the Meachams who owned it would take us far and away from the evidence of the book.

Walker’s Critical Pronouncing Dictionary is an interesting choice of lexical bible. The Meachams might have owned a copy of any edition of Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language (the first edition was published in 1755), especially the new revision by the Reverend Henry Todd (who has already made an entrance in this blog) in 1818, or even Noah Webster’s An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828). If the Honorable James Meacham was an owner of the book, he was about eighteen years old when Webster’s big dictionary appeared. But if cost were a factor — Todd’s Johnson ran to four volumes, and Webster’s dictionary was prohibitively pricey — then the Meachams might have relied on Webster’s more accessible A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806). Walker’s Critical Pronouncing Dictionary wasn’t the period’s default dictionary.

Walker started life as an actor, not a lexicographer, but he was no star on the stage, so turned to other work while keeping a foot in the theatrical door. At one time Walker worked with David Garrick at his famous Drury Lane theater. He also trod the boards in Dublin, with Thomas Sheridan. Walker was a minor player in the drama of his day. Like Sheridan, he developed a reputation as an elocutionist, that is, someone who taught others to pronounce words “correctly,” like actors. Like Sheridan, he produced a dictionary that amplified his elocutionary reputation. As a bonus, the Critical Pronouncing Dictionary also defined the words subjected to Walker’s idiosyncratic but popular system for indicating pronunciation in his dictionary’s entries. It would take another fifty years or so for the International Phonetic Alphabet to glint in its creators’ eyes. Walker’s dictionary became a prime authority on English words, “the statute-book of English orthoepy [correct pronunciation],” as a reviewer in The Atheneum put it, so not a bible, exactly, but still laying down the law, reason enough for the Meachams to own a copy.

The Meachams’ copy of Walker’s dictionary marks a step forward in the history of publishing — theirs was a very model of a modern reprinting of an already familiar book. Collins and Hannay produced the first stereotyped edition of A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary. As Walker defines it, stereotype means “sold plates of type-metal, bearing an exact resemblance to pages of printers’ types, and used for printing books,” an advance in printing because it made a reproducible impression of type that freed printers from reserving type for the printing and reprinting of a particular book. The Meachams’ dictionary may not have been at the cutting edge of lexicography, but it did represent printing innovations worth noting.

The book includes the following advertisement:

The importance of the Stereotype art, in its application to literary works of acknowledged reputation, has been long known, and so justly estimated by the Publick, that no additional arguments in its favour are at this period necessary, especially when adapted in works of this kind here exhibited. In both England and France, the most popular books have received this form of printing; and they are now judiciously preferred to editions printed in the ordinary manner. In our own country, also, the experience of several years has given practical proof at the utility of this art; a considerable number of works being already stereotyped, and repeated editions of them having been demanded by the Publick.

No need for additional arguments, yet Collins and Hannay made one any way, which suggests that stereotyping wasn’t yet fully appreciated by the Publick, though as reprints became routine and book prices decreased as a result, they would come around. Perhaps the Meachams, Yankees to the core, bought their family dictionary at just the right time and at just the right price.

Leave a Reply