This post is part of a series of reflections from the “Midwest Indigenous Cartography” project, which is an ongoing initiative that seeks to explore Indigenous worldviews, conceptions of cartography, and map-making practices, particularly in the Midwest.

The West has defined a map as a visual representation of a geographical space. Different styles have different uses, advantages, and disadvantages. There might be different styles, where one aspect is ignored and another prioritized. An example is the Mercator projection, where areas towards the poles look much more significant because putting a sphere on paper without distortion is impossible Greenland, on Mercator projection maps, tends to be about the size of Africa when the African continent is about 14 times larger. But any one given map is only partially correct, and maps are more subjective than many people believe.

Maps should be considered political agents. Oklahoma’s panhandle originated from a compromise to protect slavery. The wampum belts discussed in a previous blog post were made to detail treaties and alliances. Essentially, lines on paper determine your rights and which nation claims and taxes you. Dividing land and land ownership by the government is a little more complicated, but you can walk a mile and be in a new country in some places. In Bloomington, I’m closer to Toronto than DC. This affects every part of our lives; nationality can be a privilege.

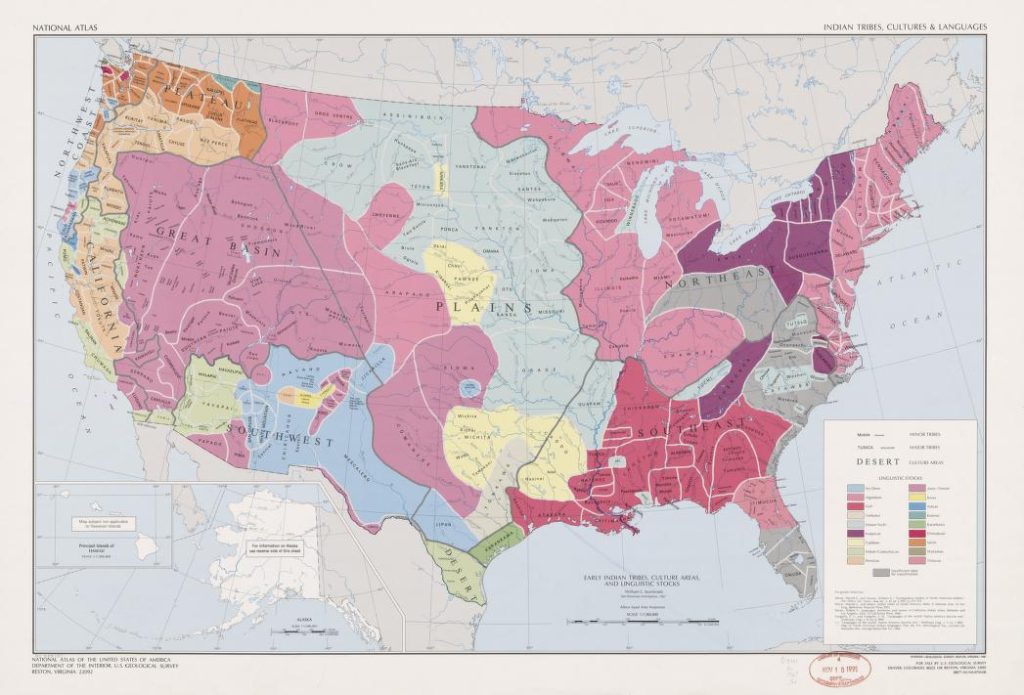

Ultimately, this is a very narrow view of what maps are and can be. There’s evidence that wampum was used for beading mnemonics that explain the land, treaties, and alliances, which would indicate the ground they can go on (Lewis 176). While a wampum belt is not a map according to the West’s definition, it performs the essential functions of a map. Maps communicate some information about the land. They could share anything, such as those who live there, important typological features, political landscape, etc.

This research project sought to show examples of Indigenous cartography. However, pre-colonization, there were no Western-style maps. The closest I found was from Jim Enote, a Zuni elder. He showed maps focused on the relation of typographical features to each other, as opposed to the scale. But this style is not found elsewhere. Enote has said, “More land has been lost to mapping than conquest” (Vaughn 3:15), which is a consideration to remember as we think of maps differently. Another notable map type, one that’s more pan-Indian, is song. Enote talks about this often, as the road around the Zuni are primary highways that provide no information about where you are or where you are going. But historically, those have been Zuni trails that have songs about where they are, where they are going, and who is there with them (Vaughn 7:02).

Enote has another exciting way of explaining why paper maps shouldn’t be seen as the only way. He asserts that they cannot convey the human perspective and experience. Seeing the world top-down doesn’t show the whole story. There’s no memory in a modern map, according to Enote (Baker 2021).

Now, many organizations focus on preserving Indigenous knowledge and tribal lands through cartography. Most notable is the Indigenous Mapping Collective, which hosts the Indigenous Mapping Workshop to help Indigenous folks map their ancestral lands. Countermapping is making maps that are meant to subvert the larger power structure (Hodgson 79). How indigenous people see land and understand the historical lands their nation resides in entirely differs from how governments and oppressors see it. Countermapping also allows traditional ways of seeing the world to connect with the modern world. Connecting the songs into visual pieces of information. It allows Nations to reclaim space.

So what is a map? A map is a representation of some features of the land. It doesn’t have to be visual or have rigid gridlines. A map is just what you make of the land.

Works Referenced

Barker, Diane, et al. “Counter Mapping.” Emergence Magazine, 5 Oct. 2021, emergencemagazine.org/feature/counter-mapping/.

Hodgson, D. L., & Schroeder, R. A. (2002). Dilemmas of Counter-Mapping Community Resources in Tanzania. Development and Change, 33(1), 79-100. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00241

Vaughan-Lee, Adam Loften & Emmanuel, et al., directors. Counter Mapping. Emergence Magazine, 23 Nov. 2021, https://emergencemagazine.org/film/counter-mapping/. Accessed 3 May 2023.

For more resources related to the Midwest Indigenous Cartography Project, see our project bibliography on Zotero.

Cheyenne Brenton is a research assistant on the Midwest Indigenous Cartography Project. They are a junior at Indiana University studying Philosophy.

Leave a Reply