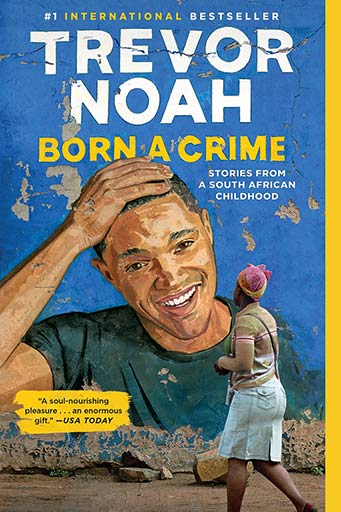

Late this summer, I was contacted by colleagues in the Kelley School of Business. The Kelley Common Read book was going to be Trevor Noah’s Born a Crime – did the University Archives have anything that could bring Noah’s story closer to home?

I knew a little bit about the movement to get Indiana University to divest from South African companies in the 1980s to protest apartheid, but I had never taken the time to dig into the whole story and was eager for this opportunity. What I learned was – oh my goodness, YES, we have a TON related to South African divestment, student protests, and the work of faculty and staff to move toward a more thoughtful and ethical investment strategy in South Africa.

First, What is Apartheid?

Simply put, apartheid was a system of institutionalized racism that was in place in South Africa for nearly 50 years from the late 1940s until the early 1990s. It put South Africa’s minority white population in power in every sense of the word. Segregation in every area of life was staunchly enforced; Black residents of the country were required to always carry an internal passport; the ethnicity of a person dictated where they could live, who they could marry, whether they could vote, where they could go to school, etc. Noah’s book provides readers with a glimpse of what it was like to grow up both under this kind of oppression and as “a crime” – the product of a Black mother and white father.

Indiana University & Divestment: 1970s

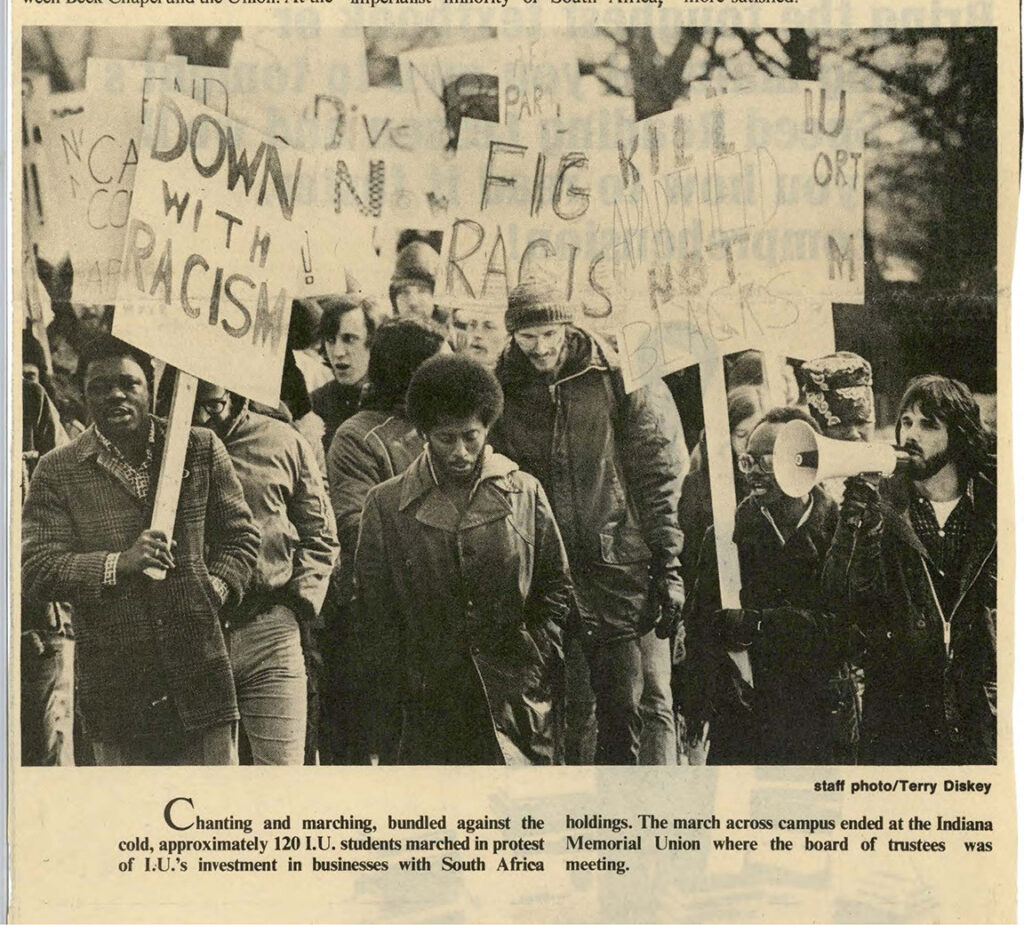

In Indiana University records from the late 1970s, we see evidence that students, staff, and faculty were really beginning to take notice of apartheid and South Africa, and they objected to Indiana University profiting from the brutality of the system through investments with companies that did work in the country. They added their voices to calls coming from throughout the U.S. to eliminate investments in South Africa, hopeful that loss of money would pressure its leaders to end minority rule.

In a November 10, 1977, Indiana Daily Student article, reporter John Butwell dug deep into the work of three IU student groups working on the university’s and the IU Foundation’s divestment of more than $5.7 million in South African companies. (N.B. – the Foundation is separate from the University and serves as its fundraising arm.) The active groups included the Student Coalition Against Racism (SCAR), the Bloomington South Africa Committee, and the Black Christian Student Fellowship, though they had the support of several other student organizations on campus, including the Latin Alliance of Midwest America (ALMA). They worked together to collect signatures for a petition demanding IU’s divestment.

The response at the time, according to Butwell’s article, was that IU officials felt that their divestment would have little effect on the companies’ policies, given how small their investments were in the grand scheme of things. Even IU’s beloved Herman Wells, then University Chancellor but also a member of the IUF investment committee, told Butwell that before he considered divestment, he’d want to know more about the extent of U.S. companies’ holdings in South Africa, saying, “I read somewhere that many companies listed as being in South Africa don’t actually manufacture there, but just sell small amounts of goods there.” (That was indeed the case, Butwell’s research showed.)

But also, some argued, it was possible these U.S. companies could make headway in undermining apartheid by adhering to what was known as the Sullivan Statement or Sullivan Principles, developed in 1977 by U.S. Civil Rights leader and General Motors board member Reverend Leon Sullivan. The Sullivan Statement was a pledge for corporate responsibility – for companies to use nondiscriminatory employment practices, to train Blacks for more highly skilled jobs and to improve Black workers’ health, housing, education, recreation and transportation facilities. (In 1999, Sullivan helped unveil the updated and expanded corporate code of conduct known as the “Global Sullivan Principles.”). Butwell’s article shared that of the 40 South African companies with which IU and the IUF invested, only six had signed the statement as of April 1977. Response from the IU Board of Trustees was mixed, with some members saying yes, social effects of IU investments should be considered, but ultimately their obligation to IU should come first. Trustee Carolyn Gutman, however, told Butwell, “There are always many thousands of kinds of investments to make – it seems we could invest in something which did not have serious political ramifications, even if the (political) investment had an amazingly large return.”

The trustees had an opportunity to learn, as members of the University Faculty Council organized a seminar for the purpose of educating them about apartheid in the spring of 1978. The information presented at the seminar must have been compelling (perhaps coupled with campus protests and continued pressure by the IU community), as by June of that year, the trustees had approved a new policy surrounding investments in countries doing business in South Africa. The policy, however, fell short of outright divestment. Rather, it recognized the concerns of the University community and affirmed that the University would place pressure on corporations to adopt a corporate code of conduct (whether it be the Sullivan Statement, the European Economic Community codes of conduct or the equivalent). If companies failed to do so, IU would then divest and make no further investments in the corporation until such steps were taken.

So progress, but the IU community continued to keep an eye on the situation in South Africa and maintain pressure on university leaders.

Indiana University & Divestment: 1980s

In 1985, campus activity regarding South Africa and apartheid made headlines again as the IU Student Association (predecessor to IU Student Government) adopted a resolution denouncing apartheid and called upon IU to once again reconsider its investments. Additionally, IUSA asked that the University advise the federal government of IUSA’s concerns and urge lawmakers to end all US involvement in South Africa until apartheid ended.

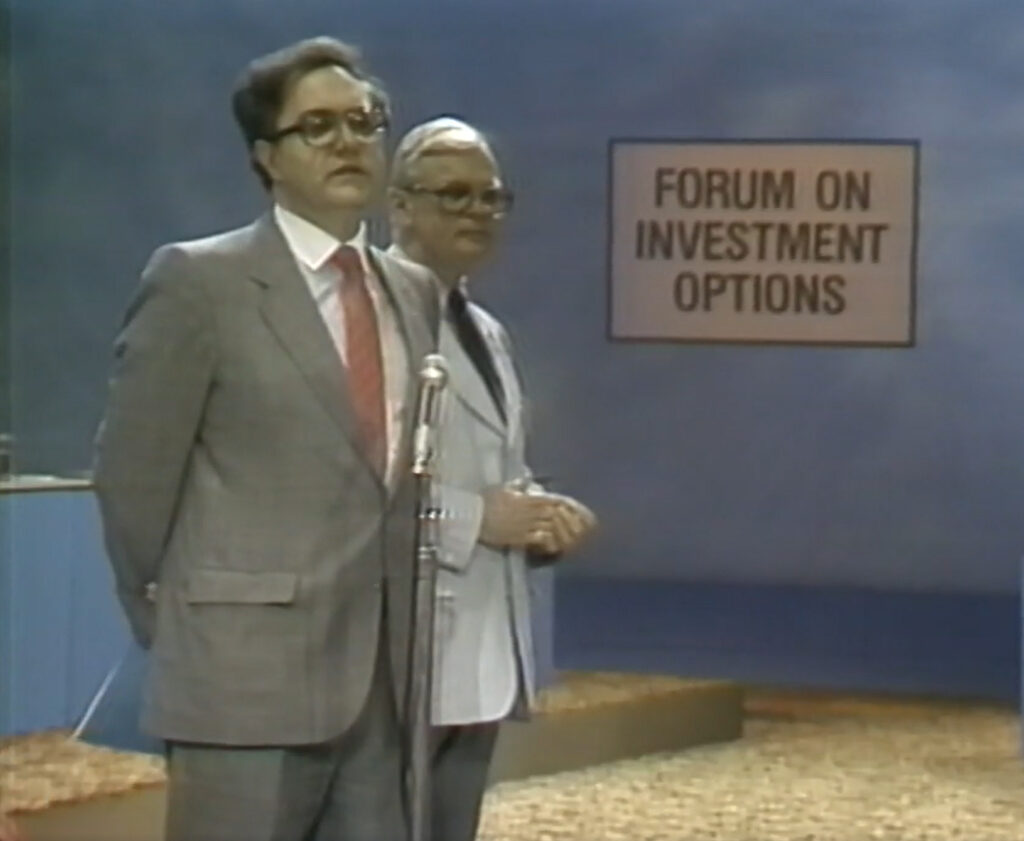

One result from the resolution was an educational forum about apartheid that once again focused on educating IU’s trustees about the issues. Organization of the forum largely fell to Professors Robert Bareikis (Germanic Studies) and Patrick O’Meara (African Studies) – the latter born and raised in South Africa until the 1960s. Together with student leaders and other faculty, they planned the day long “Investment Responsibilities in South Africa: A forum for The Indiana University Board of Trustees,” held September 20, 1985. It was broadcast throughout the Indiana University system and at IU Bloomington, it could also be watched on the big screen at the IU Auditorium. Speakers for the day included South Africans Dumisani Kumalo and Bishop Desmond Tutu (via telephone), Ford Motor Company’s William Broderick, Congressman and House Subcommittee on Africa Chair Howard Wolpe and more. At the forum, 1984’s Nobel Peace Prize recipient Bishop Tutu emphasized the importance and necessity of outside governments to help end apartheid, telling the IU audience, “I myself believe that our last chance for reasonably peaceful change in South Africa will lie in the attitude and action of the international community.”

COOL RESOURCE ALERT! Through the efforts of IU’s Media Digitization and Preservation Initiative, tapes of this event have been digitized and are freely available in Media Collections Online!

Faculty and student groups provided university administrators with recommendations on how to move forward with South Africa but there was still a great deal of concern from IU’s leaders about balancing the university’s fiduciary responsibilities with moral responsibilities. Trustee Joseph Black told IDS reporter Leah Lorber, “I’m terrified about divesting from Eli Lilly. They’ve given us close to $50 million for (IU-Purdue University at Indianapolis) in the last 10 years. You stop and think all that Lilly’s done for us….If I were a corporate executive in these corporations, I would think ‘Indiana doesn’t want us around.’” (IDS, “Divestment could affect recruiting, scholarships,” October 29, 1985)

At their November 1, 1985 meeting, the Board of Trustees once again voted against total divestment of South African companies. Instead, in an updated policy, they laid out a list of expectations for companies who were required to respond through submission of a written acknowledgement of compliance. The IU Treasurer was charged with reviewing the acknowledgements and providing the Investment Committee with recommendations regarding investment or divestment.

Students continued to keep an eye on the University’s work in this area, and in April 1986, a group of about forty students organized in Dunn Meadow and began to erect shanties. The shanties, according to IDS reporter Melinda Stevenson, were “meant to resemble the bantustans in which the apartheid system forces many South African blacks to live.” (IDS, “Few witness shanty dismantling,” December 2, 1986). Throughout the month, students staged protests and erected additional shanties. When Little 500 weekend came around, protestors and the IUSA distributed yellow armbands, asking students to wear them throughout the weekend to raise awareness of apartheid. Despite vandalism and threats, protestors remained in the Dunn Meadow “Shantytown” through the school year, summer, and into the next fall semester. The Assembly Ground Advisory Committee, formed by IU’s Dean of Students Michael Gordon, recommended the University allow protestors to remain but in December, the protestors begin disassembling the Shantytown with plans to move their protest efforts indoors through a series of debates at the residence halls.

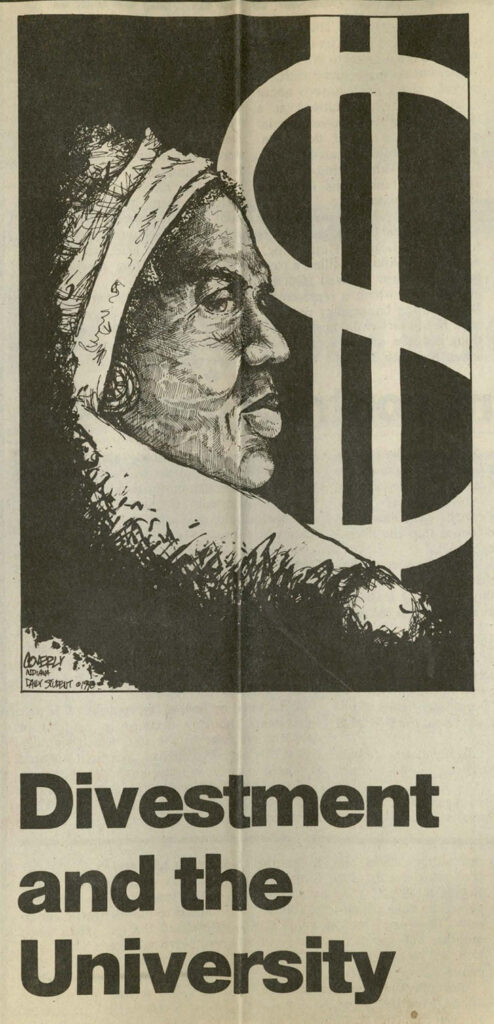

In the following years, campus groups continued their work to encourage the trustees to take stronger actions. In April 1989, the IUSA and the IU Anti-Apartheid Committee submitted a “Report to the Indiana University Trustees on the Issue of Divestment from South Africa.” The report outlined the problems with IU’s policy on South Africa, gave a timeline of significant events in South Africa from 1986-1988, and provided excerpts of South African policies of fellow Big Ten universities, which indicated several had already moved to complete divestment while others were well on their way.

And into the 1990s

In a February 16, 1990 “Point/Counterpoint” column for the IDS, trustee Harry Gonso explained the steps the trustees had taken to that point to hear arguments from both sides of divestment. He wrote that the board wanted to speak out against apartheid and that it indeed “justified the adjustment of the normal investment criteria.” But to pull completely out would have meant they had spoken out only once; by moving forward with companies, they could communicate to these U.S. companies “that as one of the finest universities in the world, we cared about their social responsibility, we expected them to combat racism in South Africa, and we wanted reports as to their activities in South Africa…had we divested or disinvested, we would have spoken just once saying, in effect, that we were against apartheid and we wanted to contribute to the dismantling of U.S. involvement in South Africa (never mind that the vacuum would be immediately filled by investors from Japan, Germany and elsewhere). Thereafter, having said that, our ability as a shareholder to communicate our opinions and values would have been gone.”

In his “Counterpoint” article, student Joe Kulbeth, chairperson for IUSA’s Anti-Apartheid Committee, recognized that IU had made progress. In 1982, it had $5 million invested in companies doing business in South Africa. At the time of writing, IU had reduced its investments to under $900,000 in eight companies (total university investments were approximately $55 million). But he called for IU to finish its work and direct the money elsewhere.

Gonso and the trustees were once again listening, it seems. In April he shared the draft of a new trustees policy with IUSA President Jerry Lee Knight. The policy addressed both direct and indirect investments and how they would approach each of these. For direct investments, IU would not only ensure that companies had a statement of principle for working in South Africa but also that the product or service produced by the company would benefit ALL people of South Africa. Further, the products could only be “benign” in nature – no automobiles, trucks, guns, ammunition or similar products that could be used by the South African military. Knight, however, told the IDS that he thought the new policy was possibly weaker than the 1985 policy, noting “I’m almost afraid that it’ll open loop holes that trustees in the future can take advantage of.” (IDS, “IU rethinks apartheid investment,” May 5, 1990). The policy went forward and was approved at the June 9, 1990 Board of Trustees meeting. While the students may have continued to have misgivings, the Indianapolis Business Journal held up IU’s new policy as “worth imitating.” (IBJ, “IU’s new investment policy re: South Africa is worth imitating,” May 14-20, 1990)

The End of Apartheid

Nelson Mandela, imprisoned in South Africa in 1962 for his role in attempting to overthrow the apartheid government, was released in 1990 amid growing domestic and international pressure to release him. It was one of the first steps taken by South African President Frederik Willem de Klerk to begin dismantling the system of apartheid in his country. There were several years of negotiations, but apartheid officially came to an end in 1994 with Mandela, representing the African National Congress, elected South Africa’s new president.

In 2013, the Board of Trustees voted to revoke and rescind several policies that were no longer relevant to or affecting the University, which included the 1985 “Policy on Investments in Corporations Which Have Business Operation in South Africa” as well as its 1990 amendment.

This is obviously a very broad overview of a very complicated subject that included many other players and important events on campus. As I worked with our Kelley colleagues, I scanned a lot of the documents I came across for their use in Kelley events, including those cited in this post. They are freely available in a OneDrive folder at https://go.iu.edu/43Vq. File names include the collection or accession number, along with the folder title, when applicable. Several items had been previously digitized, such as the IUSA resolutions and Bloomington Faculty Council documents and can be found in a separate folder. As always, please do reach out with any questions or if you would like to view any of these materials in person!

Leave a Reply