A display of indigenous corn and ceremonial gourds grown by Stacy Featherstone. Image Courtesy of Carey Champion

“Wylie House Museum is shifting its focus from being a producer of heirloom seeds to tracking heirloom seeds,” Director Carey Champion explained at the beginning of Indiana Heirloom Seed Savers Showcase & Exchange on Saturday, March 5. Though Wylie House Museum intends to maintain their garden, Champion notes it has been “a victim of city deer” and that fencing the garden is somewhat complicated due to the historic nature of the property.

This first Indiana Heirloom Seed Savers event was organized by IU graduate students from Dr. Olga Kalentzidou’s Urban Agriculture course: Gabrielle Alicino, Corryn Anderson, and recent graduate Jessie Wang. They gathered several panelists from around the state to discuss seed saving. “Our goal with this project was to uncover more heirloom stories, build a web of connection between savers across the state,” Alicino explained.

next to the panel of speakers: Stacy Featherstone, Emma Ruf,

Jennifer Lambert, Lauren Volpp, and Luiz Andre Bispo de Jesus.

Image courtesy of Melania Majowicz

Anderson opened the discussion with the Land Acknowledgment, adding that some of the participants and heirloom projects revolve around “the preservation, rematriation, and cultivation of Indigenous seeds, plants, and stories.” The students told the audience that seed saving is vital for biodiversity, and presented the image of immigrants arriving in the United States with seeds in their pockets. Seeds provide “food sovereignty and cultural preservation and reconnection.”

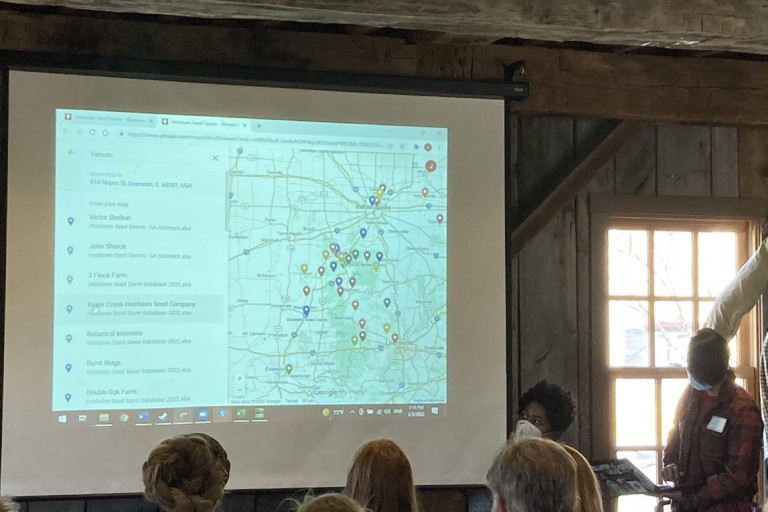

Jessie Wang, the data specialist of the group, presented the Indiana Seed Savers' map, a display of Indiana with markers for each seed saver. Soon, the map will live on the Wylie House Museum’s homepage. Wang said map users will be able to look up not only seed savers but specific plants.

Why save seeds?

The seed savers on the panel consisted of a variety of people: Stacy Featherstone, a dedicated seed saver working with several heirloom seed organizations and Females Farming Forward; Emma Ruf, a youth leader in the Central Indiana seed saving movement; Jennifer Lambert, a Master Gardener (MG) educator and co-founder of the Seed Committee; Lauren Volpp, a farmer instrumental in the Plant Truck Project and People’s Market; and Luiz Andre Bispo de Jesus, Hilltop Gardens’ employee and seed saver with a special interest in Brazilian, medicinal plants.

Seed saving starts with a personal connection. Several of the panelists were inspired by family. Bispo de Jesus was taught directly by his grandmother in Brazil where they started a community garden. Ruf, a high school student, started when her family found containers of seeds while clearing out her grandmother’s house. Using the “paper towel” method, she started comparing heirlooms to regular seeds for her Future Farmers of America (FFA) project.

of Indiana. Image courtesy of Carey Champion.

Both Lambert and Featherstone noticed a knowledge deficit. For Lambert, it was when she took her Master Gardener (MG) course. It didn’t mention anything about seed saving; she is now the Indiana MG seed saving educator. Having gardened for over 30 years, Featherstone said that her passion for seed saving was sparked when she attended a Food not Lawns event on seed saving. She elaborated, “Going to that seed swap, I was the only one to show up with seeds in all of Indianapolis." She took over their website and started taking seed saving into public schools.

Volpp’s answer to starting seed saving was one word: “Poverty.” After she got a community plot in Bloomington, she heard Wylie House Museum was giving away free seeds. “I didn’t know the significance of heirloom seeds.” She discovered that heirloom seeds were incredibly prolific. Her carrots went to seed, growing more plants. Linnea from Linnea's Greenhouse shared with her what heirlooms were, and Volpp has been committed to them and saving seeds ever since.

Defining Heirloom

“An heirloom seed is at least 50 years old and grows true to type,” Lambert answered when asked to define what an heirloom is. “You save the seed from the most desirable traits and get rid of the rest, which is hard to do because I’m a seed saver. I want to save them all.” Volpp added it’s important to be able to trace the seed back through time and to have possible records. “Linnea was trying to get me to have a relationship with the seeds. That’s when it becomes an heirloom. I’m going to keep it now that I have a relationship with it.”

Bispo de Jesus emphasized the importance of keeping the seeds safe and sharing them. He also talked about how he marks his plants after he selects the one with the traits he wants to carry forward. “Because they are food,” he gives away seeds he doesn’t select for, so that other people may grow them. The seeds of one of the plants that he brought with him were one hundred years old.

Featherstone shared, “To me, some of the keywords are heritage, lineage, tribal, family.” She spoke about the importance of keeping seeds in the family, handing them down through the generations. Ruf agreed. “My story was passed down through my great grandmother.” She adds, “I’m still just discovering what heirloom seeds are. I learn more every single day, and especially today, I am learning a lot.”

When asked about specific seeds, Lambert piped up about the Mary Towne bean. She visited Seed Savers Exchange in Iowa with a Master Gardener (MG) group. Seed Savers removed a seed from their cold storage and asked the group to help "grow it out" - an attempt to grow a successful yield. They gave the group from Indiana 34 seeds. The MG group successfully grew enough beans to keep 1,000 and give Seed Savers 2,000 back. Lambert continues the process, hoping to establish the bean once again. She shared, “This bean is from Mary Towne in Olympia, Washington. It crossed the Plains with her grandmother and dates back to 1858. And that’s what I grow every year.”

“It’s so important to preserve the story, the history, the dates, the names – all the things we’ll be passing down to the next generation,” Featherstone remarked. She works with multiple organizations preserving and growing out seeds. She stewards a 30-year-old collection. “Everything I do is all about the spiritual side of growing seeds and saving seeds,” Featherstone explains. She is also an advocate for tribal heirlooms, growing out seeds and restoring them to tribes. For instance, she brought red tribal corn from the Potawatomi. Continually selecting for the red corn from multicolored ears, she finds the “parent.” In addition to the red corn on display at the event, she brought Indigenous gourds. Featherstone says, “Another seed I grew out that I’m really proud of is a 26-year-old gourd.” She has two gourds: one being Navajo and the other being Hopi. “Those gourds belong to ceremonies, and they have songs in them, and they have dances in them, tears, stories - and everything that goes into ceremonies was in those 26-year-old seeds that were frozen.”

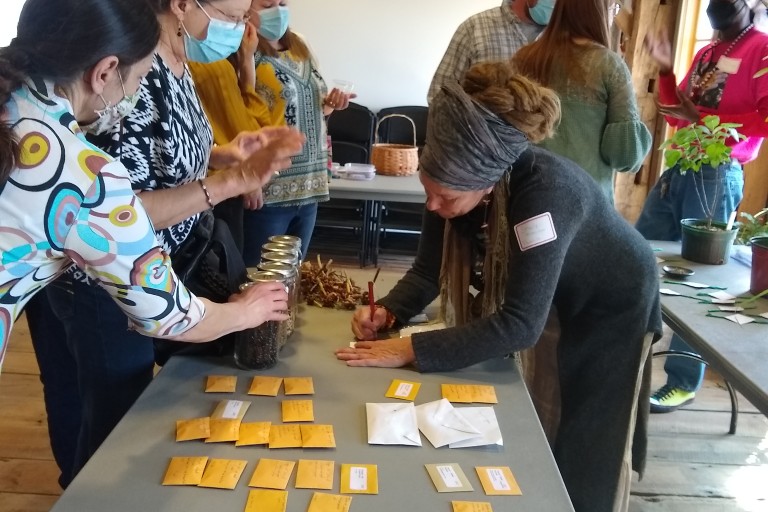

Saving and Sharing Seeds

mage courtesy of Christine Wagner

Lambert says, “People get super excited about seed saving.” She saw the pandemic increase interest, especially when seed packets in stores disappeared. More than one panelist commented on how heirloom seeds produce more robust and prolific vegetables. Volpp commented on growing the sweetest sweet potatoes ever. Using a greenhouse, Bispo de Jesus has kept some of his vegetables alive for years. He joked about talking to his plants, but the idea of being in relationship with your plants and seeds was not uncommon to hear on this panel.

Bispo de Jesus talked about giving back to the soil, “The spirit of the soil needs to eat.” Featherstone remarked that often a consumer has no idea where seeds from a seed company come from, whereas buying seeds locally assures gardeners the seeds have adapted to our Indiana soil, climate, and conditions. Lambert, however, encouraged the audience to try non-local seeds if they really want to. “You might have to grow it a couple of times in order to get one regionally adapted,” she said.

Volpp urged, “Source seeds from Indigenous folks, trying to find out the stories behind the seeds, really encouraging yourself to know so that when you’re sharing you can share the stories.” She, like others, sees people as seeds, seeds that need to be shared and cultivated.

When the discussion ended, the audience and panelists replaced tables with chairs. Gardeners, seed savers, and community members alike settled into sharing stories and seeds.