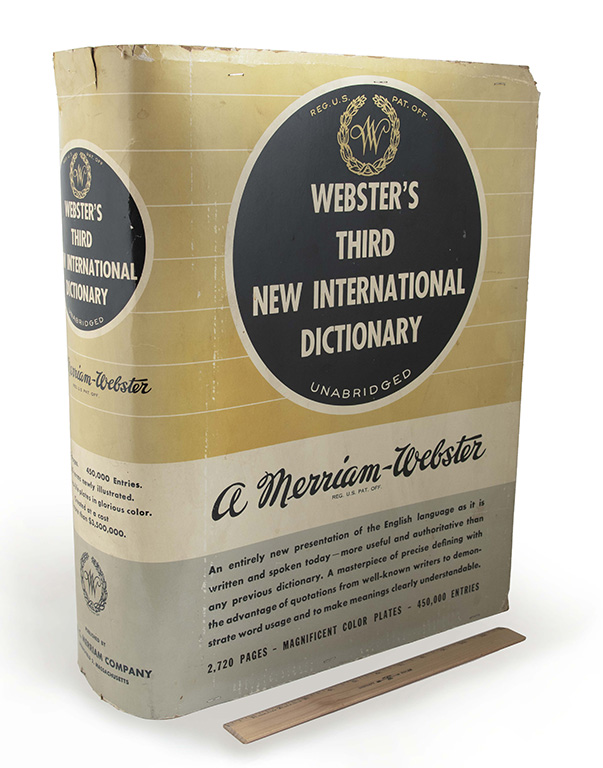

This is yet another story of a box within a box among the thousand and more boxes comprising the unpacked Kripke Collection. The first was about a little plastic box filled with notecards, but this is about a big box inside an even bigger one. Perhaps it’s not a box really, because you can’t open it. It’s a hollow replica of Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language (1961), which we usually just call Webster’s Third. It’s constructed of cardboard with pressed boards at top and bottom; the cardboard is stapled to the wood pieces — or was stapled, as time has taken its toll. It measures 20 x 15 x 6 inches, dimensions somewhat larger than those of the actual dictionary, but size serves function, in this case.

The spine notes several important features of the dictionary:

- It’s 2,720 pages long.

- It contains 450,000 entries.

- 3,000 terms are newly illustrated.

- There are 20 true-to-life plates in glorious color.

- It cost more than $3,500,000 (or $34,884,347 in 2022 dollars) to create it.

One should not be surprised that such details mattered to Merriam-Webster, publisher of the dictionary. In fact, though probably a matter of space available on the spine, the list is more reticent than publicity for Webster’s Third overall. The permanent editorial staff numbered more than 100, 33 of whom had doctorates and 62 had master’s degrees; there were more than 200 external consultants; there were secretarial and clerical assistants, as well. The editors added more than 100,000 words and senses to the preceding edition (published in 1934). Etc.

According to text on the front of the box, Webster’s Third constituted

An entirely new presentation of the English language as it is written and spoken today — more useful and authoritative than any previous dictionary. A masterpiece of precise defining with the advantage of quotations from well-known writers to demonstrate word usage and to make meanings clearly understandable.

The publishers couldn’t say enough good things about their dictionary.

Philip Babcock Gove, the dictionary’s chief editor, aligned lexicography with linguistics and expected Webster’s Third to be revolutionary, a descriptive dictionary — one that accounts for how people use words — rather than a prescriptive dictionary — one that tells users how they should use words. It was, in a sense. It ignited a revolution among dictionary users, many of whom rejected Webster’s Third, which energized its competitors and even prompted new dictionaries, like the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (1967) to enter the market, events narrated deftly by Herbert C. Morton in The Story of Webster’s Third: Philip Gove’s Controversial Dictionary and Its Critics (1994) and David Skinner’s The Story of Ain’t: America, Its Language, and the Most Controversial Dictionary Ever Published (2012). James Sledd and Wilma R. Ebbitt’s Dictionaries and That Dictionary: A Casebook on the Aims of Lexicographers and the Targets of Reviewers (1962) collects all sorts of documents of the controversy, including write-ups from which I took the facts above. In any event, there are sometimes dangers to believing your own marketing.

The saga of the 1960s wars of the dictionaries distracts us, though, from an interesting aspect of the Webster’s Third replica box. It should remind us that dictionaries are material objects. Of course, we know this, because we have used them as doorstops and booster seats, because when we don’t use them enough, we pile other books on top of them. Webster’s Third is so material, in fact, that one finds it difficult to hold it open on one’s lap: it weighs in at 10½ to 15 pounds depending on the binding and the paper, that is, heavier than your average baby (which will fit comfortably on most adult laps); it’s also bulky, not as bulky as the replica, but at 13 x 10 x 4½ inches bigger than most other books. In the 1960s, it could be bound in buckram or Fabrikoid, with regular paper or India paper. Back then, if the one-volume version was too much to handle easily, you could buy a two-volume version. And while you were considering which form of Webster’s Third you preferred, if it was the single volume, you might consider a bookstand, too.

Big books don’t wear well without book stands or other special care. They don’t fit on the little plastic stands behind bookstore windows — the sloppy front cover hangs over the stand, pulling at the spine and pages, which damages the book. Sloppy is not a good look for a dictionary. Also, Webster’s Third was expensive. In 1965, the version with cheaper binding and paper cost $47.50 or nearly $450 today. People don’t pay hundreds of dollars for massive broken-down unabridged dictionaries. If a real Webster’s Third went into the window, it was a loss, one less dictionary to sell. Also, the replica makes Webster’s Third look even bigger, more impressive than it actually was. In a show window, it makes the marketers’ point.

Dictionaries are more than intellectual tools, more than books one can read, as some who are intensely interested in meanings, uses, and histories of words do and have done across cultures. They are objects of our attention, often our inattention, but we place them, walk around them, shelve them, look at the shelves and see them there. They are parts of our spatial, ontological existence, as well as our intellectual lives.

The replica was one of Madeline’s favorite things. She objectified it, too — showed it off, a dictionary novelty. She kept it on her fireplace mantel for many years. Now, it’s still a thing in a large room with boxes filled with things that have to be sorted through, organized, listed, processed, catalogued, and stored. Later on, visitors to the Lilly Library will request those things, and staff will retrieve and deliver those things in the reading room. Then, the books or whatever material will be, not mere objects, nor only objects of admiration, but objects of research. Among them all, the replica box of Webster’s Third is an object by design.

Leave a Reply