Fall 2018 the University Archives partnered with Media School professor emeritus Ron Osgood and his new Honors Course Archival Storytelling. His students spent several class sessions in the Archives researching a topic of their choice and crafting a blog post for inclusion here! Some students chose to provide overviews of collections while others dove into specific bits of IU Bloomington history, but all seemed to enjoy the experience. We’ll be sharing these posts in groups over the next few weeks. In order to ensure the student’s voices are heard, Archives staff did minimal editing on these pieces. Thanks to Prof. Osgood and his class for these great pieces!

______________________

University Removal Question by Sarah Richter

Indiana University is such an integral part of Bloomington. It is hard to imagine what the town would be like if the university was never here. Likewise, it is hard to imagine what Indiana University would be like without our beloved B-town. At times, it seems like the whole town revolves around the college. The town is thriving thanks to the number of people the university has brought to it. The students have made Bloomington their home and many would not know what life in college would be like in any other place.

The ongoing renovations on the campus have brought a lot of attention to the buildings of IU. Kirkwood Hall is among those buildings that have recently been renovated. Upon doing some digging on the building’s history in the Indiana University Archives, the story of the university removal question was discovered.

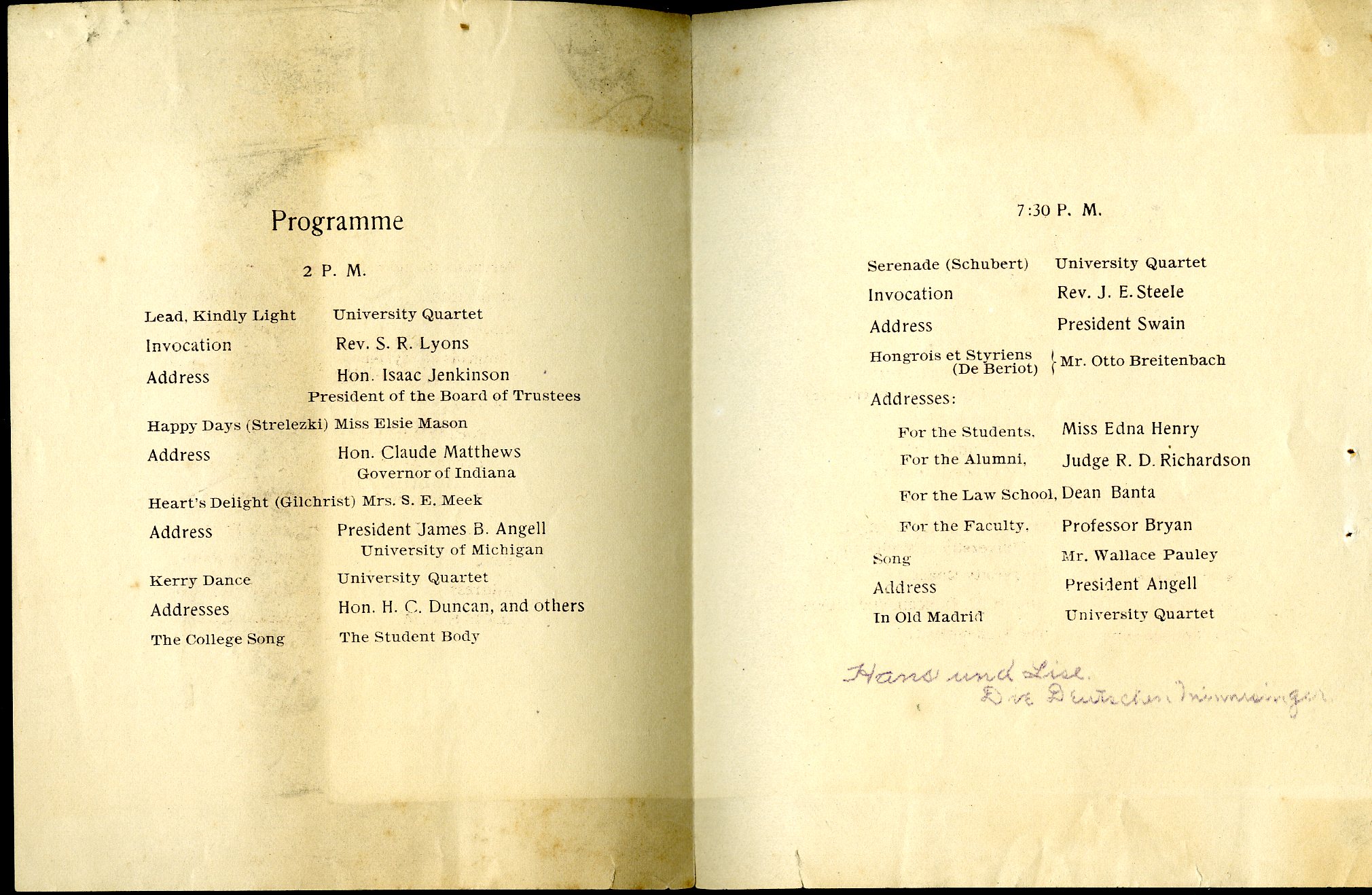

During the dedication of Kirkwood Hall, there was an unfortunate incident related to the university removal question. The dedication took place on the 25th of January 1895. The building was named after Daniel Kirkwood, who was once a professor at Indiana University. There were many people present, including students, alumni, professors, other citizens of Bloomington, as well as Company H of the 1st Regiment of the Indiana National Guard, there to escort the Governor Claude Mathews, who had also come for the event.

At the time of the dedication there had already been talk of removing the Indiana University campus and relocating it to Indianapolis. This was not a new concept and the thought had been present among Bloomington for some time. It was thought that it was just a rumor, but as time passed, the removal question became more of a serious suggestion for the university. During that time the university was rationally much smaller than it is today, but it was growing nonetheless. In 1884, there was a mere 144 students enrolled at the university and by 1894 that number had grown to 748 students. Although these numbers still feel small in comparison to the size of the university today, it was growing much faster than the university could keep up with. The campus was quickly running out of space for classes, housing, and offices. There was need for additional facilities for each of these areas. Every space imaginable was used to hold classes or offices, including basements and attics. Relocating to Indianapolis would allow the university to expand much easier than it could have in Bloomington. Indiana University would be able to take advantage of the structures already in place in Indianapolis. There would be better access to the public libraries, new laboratories, and hospitals for the medical students.

There was much to be debated in the questioning of whether Indiana University should be kept in Bloomington or moved to Indianapolis. The citizens of Bloomington were in favor of keeping the university, while many students were in support of the removal. There was debate over whether having the campus in Indianapolis would have more social distractions for the students from their schoolwork. Some thought that the parents would not like for the university to be in Indianapolis as they preferred to send their children to school somewhere quiet to focus on their studies. The centralized location of Indianapolis seemed to be more beneficial to the university, in terms of it being accessible to more people in the northern part of the state. The resources that came with the city of Indianapolis would also have been beneficial to the school. There may have been better access to lectures for the students, as well as things such a music not only for entertainment but for educational purposes. The expenses of the removal were also debated. It would have been expensive to expand with new builds in Bloomington but moving to Indianapolis would have been a great cost as well as new facilities would need to be purchases and renovated to suit the uses of the university. The overall living expenses for the students would be much higher as well, increasing the cost of attendance. There were both benefits and disadvantages to each option. In one issue of The Student (early name of the Indiana Daily Student), it is stated that “The University and Bloomington have grown up together.” There was no doubt an attachment to the town for those associated with the university, much like there is today.

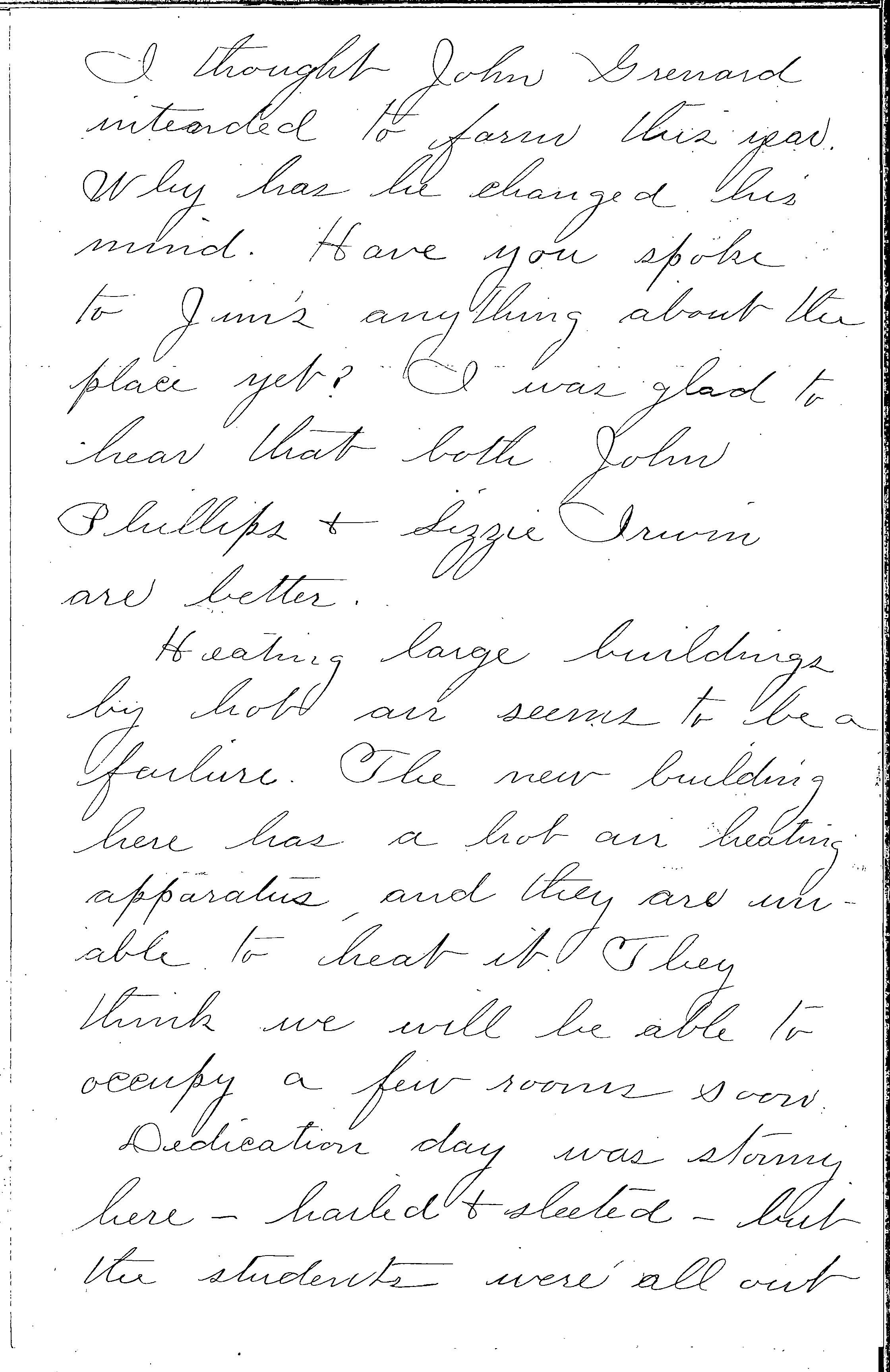

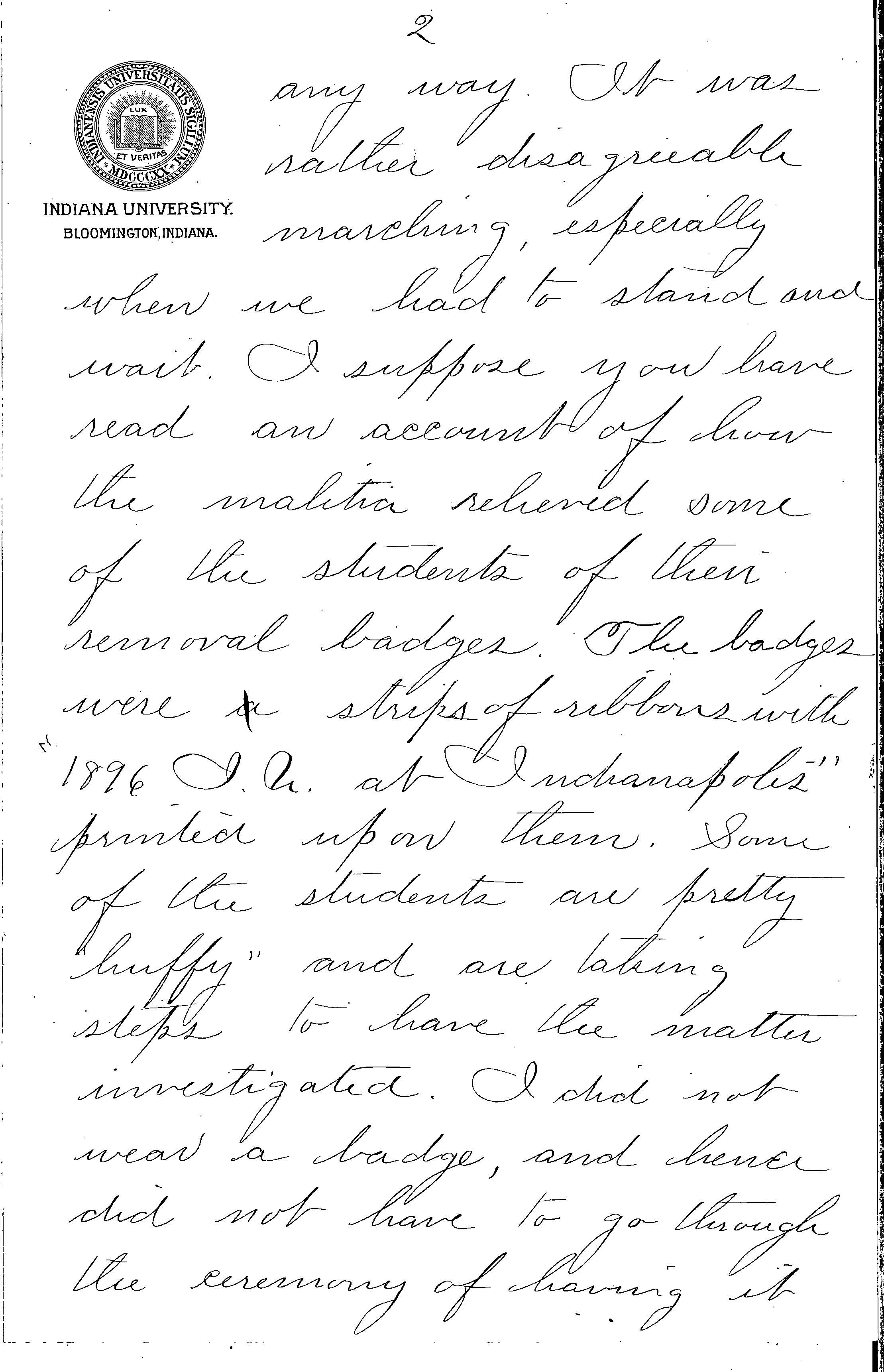

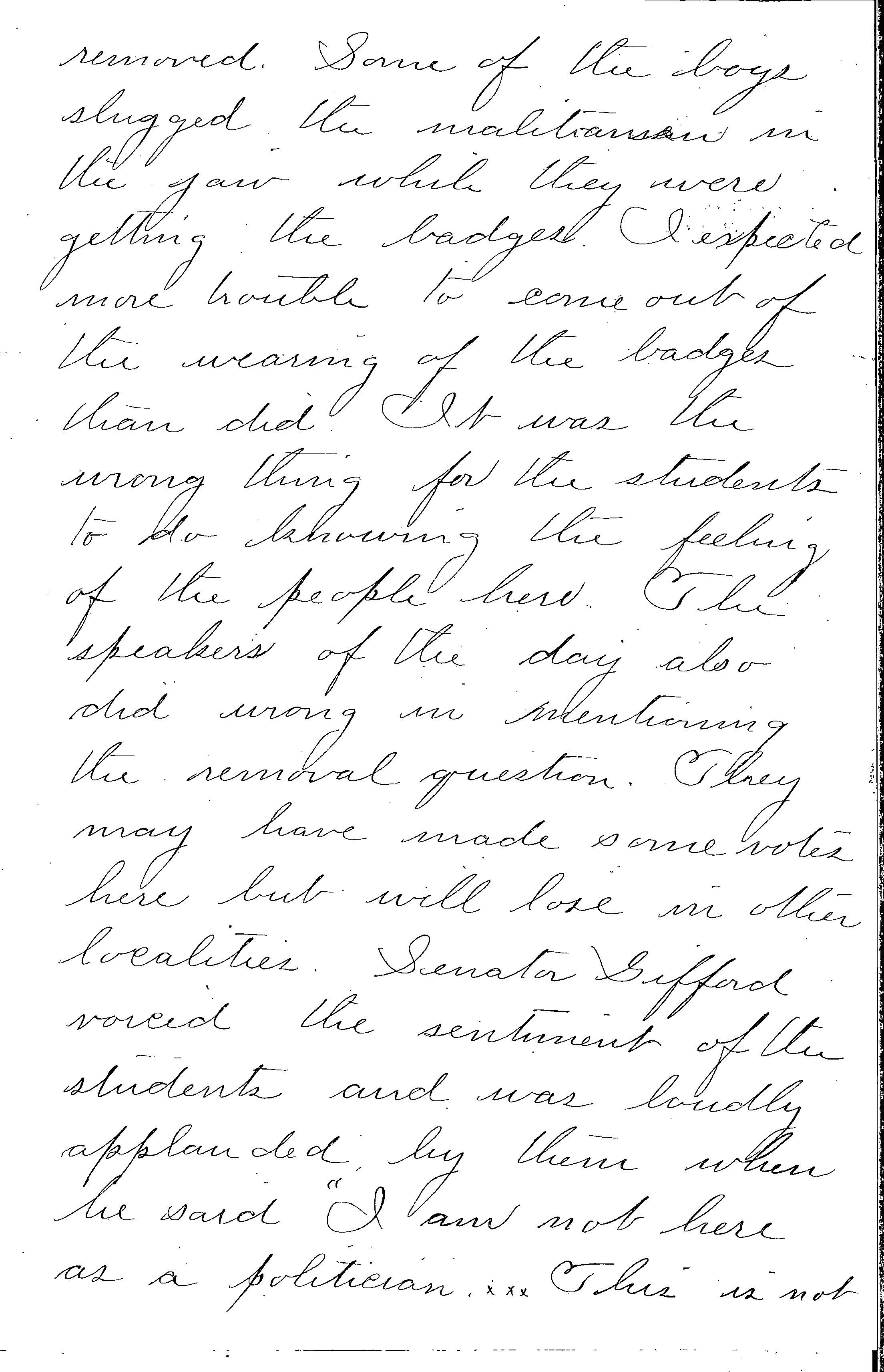

In spite of this, there was a vocal group of students in favor of removing the University to Indianapolis. They made badges that they wore made from strips of ribbon that stated “1896 I.U. at Indianapolis.” On the Day of the dedication there were chants shouted before the event of “Remove IU! Remove IU! You’re the men to put her through!” meant for all of the university’s board as well as those from the state legislature that were in attendance. The badges made by the students were worn at the dedication of Kirkwood Hall as well. Members of the Company H were instructed to remove such badges and any students who resisted were faced with the violence of being knocked down or struck by bayonets. After the incident some who spoke stated that the dedication was not the proper place to discuss the removal question. Some students wanted to have the occurrence investigated but it is unclear whether it was according to the files from the archives on this event.

This is a letter D.W. Biddle wrote to his parents detailing the incident at the Kirkwood Hall Dedication. He was a student at the time and was able to write down his firsthand experience of the event, as well as give some of his views on the removal question. There are other letters he wrote both to his parents and to others as well that can be found in the IU Archives (Collection C700). Click on images to view full size.

The city of Bloomington is obviously still the home of the flagship campus of Indiana University today. The two simply go hand in hand today despite being questioned in the past. The experience of Indiana University would be entirely different for the students if it was located in Indianapolis today. The university has grown to support itself here and as a result Bloomington has grown as well. If the question of removing the university were brought up today, it is likely that the students would view it differently and may be standing up to keep it in Bloomington instead.

______________________

IU R.O.T.C. Evolves but still Thrives by Madi Smalstig and Kasey Cassle

As a student today, you likely know of the Reserve Officers Training Corps (R.O.T.C.), however, you think that is has always been a voluntary program. Now, imagine you are a male student coming to Indiana University in the year 1964. Along with your academic courses, you would have been automatically enrolled in R.O.T.C. courses, in which you would gain knowledge about the military and be required to go through a physical training course.

Even though this military program was compulsory and unavoidable, many people took pride in their participation. The program produced well rounded students with the knowledge and experience of a basic trained soldier which was beneficial to careers within the military as well as other careers in the workforce.

Despite these beneficial factors, many people opposed it and eventually forced Indiana University’s Board of Trustees to change the program from compulsory to voluntary.

Background

Military training was offered sporadically at Indiana University from 1841 to 1874. In 1917, the R.O.T.C. program was established. For male students, the program was compulsory and for females it was voluntary. The students involved received basic hands-on military and academic training. This included 3 hours of drill, 4 hours of military training and one meeting every week. R.O.T.C. was not only required for Indiana University male students, but it was compulsory on many public university campuses across the nation.

In 1965, the university Board of Trustees decided to make the program voluntary due to public protests and the nation’s changing political climate.

The Vietnam War and the Anti-R.O.T.C.

Indiana University’s R.O.T.C. program was greatly affected by the Vietnam War and the anti-military attitude that was expressed by many Americans. Many United States citizens believed that the country should not join the war effort in Vietnam, however the United States joined the war effort in the early 1960’s by enacting the draft and sending thousands of young, male soldiers to Vietnam.

Soldiers and war supporters were subjected to hatred and ridicule. Military training which at one point had been a well-respected skill and character trait, slowly morphed into an unpopular, undesired characteristic. This lack of respect towards soldiers and military training filtered into the Indiana University campus and eventually lead to the protest of the R.O.T.C. program by students, parents, and faculty. Several groups on campus including Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and Anti-ROTC publicly protested the mandatory enrollment of freshmen into the R.O.T.C. program. Specifically, the Anti-ROTC organization was formed with the sole intention of ending the compulsory rule at IU.

The 1960s was not the first time that Indiana University’s compulsory R.O.T.C. program was protested but with the nation’s increasing questioning of war across the globe and hatred of war, the opposition became too great to ignore.

In December 1964, the Reserve Officers Training Corps Vitalization Act, or Public Law 88-647, was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. This law expanded the reserve training program by adding new facets to existing R.O.T.C. programs while also adding J.R.O.T.C. in high schools. The changes within the college R.O.T.C. programs allowed for the continuation of a four-year program as well as a new program where a male could attend a summer course instead of the first two years then complete the final two years at the university.

In addition to curriculum changes, this act also allowed for the university to decide whether enrollment in the program was compulsory or voluntary. After several months of continued protests against the compulsory program, the Indiana University Board of Trustees voted to make the program a voluntary choice for all freshmen. The change went into effect for the freshmen of fall 1965. In the following year, enrollment in the R.O.T.C. program decreased by around 60 percent.

Although the program was no longer required, it continued to be an option for all Indiana University students due to the support of former IU President Herman B Wells and other IU authorities.

The Decision and Student Reactions

It was on March 15, 1965 that the Board of Trustees decided to make the R.O.T.C. program voluntary and in the days after the community erupted. A program that had been in place for decades was suddenly changed, therefore, strong reactions for both pro and anti R.O.T.C. sides were expected of the students and faculty at IU.

A few students, like John Mead and Steve Miller appreciated the change, although for different reasons. Mead, a sophomore who had willingly signed up for the R.O.T.C. advanced program said, “I think it is good in that it dissolves the ill-feeling in students who are forced to take it. It is also bad in that students won’t become acquainted with the advantages of the program as they are compelled to under the present system.” On the other hand, Miller, a freshman, just did not understand the significance of the program for certain majors. He was happy to see the requirement disbanded because it meant that he would have more time to fulfill the requirements for his major.

These students’ opinions illustrate two of the various reasons why people wished for the program to become voluntary. Many fought for freedom from the compulsory program due to anti-war and anti-military sentiment, but some also fought for more personal issues, such as Mead and Miller. All of these efforts created enough momentum for the movement against compulsory enrollment in the program that IU decided to change its policy.

In addition, this article also proves that not all students were in agreement with the new change. One freshman, Dick Simmons, said, “I really don’t know whether I’ll go on with ROTC next year or not, but I can’t help but feel that at least one year should be compulsory, just to give you a taste of what it’s like.”

These students who were completely against the requirement, like those who created clubs like the Anti-R.O.T.C, eventually had a big impact on the rest of the student body. It wasn’t that the entire campus was against the requirement, it was that the university noticed that there were students among the protestors who were being forced to act against their own beliefs and political standings. The university was able to recognize this and change the program so students were given the option to receive training or not.

After the compulsory rule was disbanded, the group Anti-R.O.T.C., which was founded with the sole purpose of ending the mandatory R.O.T.C. program, decided to terminate their group.

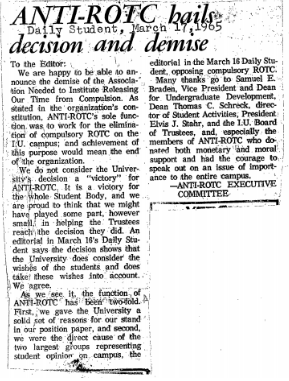

“We do not consider the University’s decision a ‘victory’ for Anti-R.O.T.C. It is a victory for the whole Student Body, and we are proud to think that we might have played some part, however small, in helping the Trustees reach the decision they did,” said the Anti-ROTC executive committee in an article published in the IDS.

They felt that the club had fulfilled its purpose by informing other students about the R.O.T.C. program and were proud of the impact they had.

Although there may have been some students who hoped to get rid of the program entirely, the focus of many students was simply to make it a choice for students to join rather than an obligation.

R.O.T.C. Continues

Since March 15, 1965, every student enrolled at Indiana University has had the opportunity to join the Reserve Officer Training Corps, but none have been required to join. Many students have completed the course work and have gone onto military careers or other careers within the workforce.

Although, starting in the early 1970s when the U.S. was in the thick of the Vietnam war, there was a period of time where of the program experienced a decrease in membership, the program continued and eventually enrollment increased. According to an article from the IDS, the Army R.O.T.C. program reached an all-time low enrollment of 58 freshman and 121 total students and the Air Force R.O.T.C. program also had staggeringly low numbers of 94 total students in the fall of 1973. In 1974, however, the program began to rebuild and, that year, the Army R.O.T.C. program had 82 freshmen enroll, which bumped the total number of students to 156.

About three years after the change in 1968, Herman B Wells, then serving as interim President, gave a speech addressing the program and its policy changes and how they affect the university as a whole. He emphasized that, “R.O.T.C. continues to be offered at I.U. because many of our students desire officer training in conjunction with their college education,” and it, “in no way interferes with conscientious objectors any more than, for example, the existence of our School of Medicine interferes with students who are Christian Sciences.” Throughout 1968, the SDS continued to protest the R.O.T.C. program. Despite this, President Stahr and university administrators, including Wells as Chancellor, supported the R.O.T.C. program and its continued presence on Indiana University’s campus. They also allowed the SDS and other organizations to continue to assemble and bring forth their concerns in peaceful manners. (Subject File 1967-1969, Student Affairs)

The words spoken in Wells’s speech still ring true today. The R.O.T.C. program has continued through the ever-changing political climate of the nation and the world, and, although students today are not required to enroll in the R.O.T.C. program, the program still gives choice to the students and plays an important role in the culture of the university.

Leave a Reply