Fall 2018 the University Archives partnered with Media School professor emeritus Ron Osgood and his new Honors Course Archival Storytelling. His students spent several class sessions in the Archives researching a topic of their choice and crafting a blog post for inclusion here! Some students chose to provide overviews of collections while others dove into specific bits of IU Bloomington history, but all seemed to enjoy the experience. We’ll be sharing these posts in groups over the next few weeks. In order to ensure the student’s voices are heard, Archives staff did minimal editing on these pieces. Thanks to Prof. Osgood and his class for these great pieces!

______________________

The Depictions of the Tragedy of Woyzeck at Indiana University by Adam Lu

Died of typhus at the young age of 23, Georg Büchner, the young, brilliant German dramatist’s legacy was limited to a handful of stories and fragments. However, out of the manuscripts he left, one unfinished tragedy became one of the most fascinating theatrical puzzles to put together.

The play, Woyzeck, was speculated to be started by Büchner in mid-1936, about half a year before his decease. The left 29 written scenes, without a particular intended order from the author, collectively created an open-ended tale subject to independent interpretations and rearrangements from other playwrights. Dozens of playwrights have since founded their own versions of Woyzeck to put on stage and screen, and one of them, adapted by Daniel Kramer, was used for the production at Indiana University during the 1999-2000 season.

The inspiration of Woyzeck very likely came from the real-life case of Johann Christian Woyzeck, who lived in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Germany. Born in 1780 and raised in Leipzig to be a wig-maker, Woyzeck lost both his parents before 13 and had lived his life in or near poverty since then. He was hired by mercenary during the Napoleonic wars from 1803-1815. When he returned to Leipzig after the wars, Woyzeck maintained a living by taking odd, low-paid jobs, often falling in trouble with the law due to alcohol abuse. People believed him to be a madman, displaying irrational, schizophrenic behavior.

In 1818, Woyzeck attempted a relationship with a widow named Johanna Christiana Woost. The relationship probably didn’t progress as Woyzeck thought, as he was often frustrated because Woost went out with other people. On June 2, 1821, when Woyzeck saw her walking with another man, he chased after her to her house and stabbed her to death with a knife recently fitted with a handle. When the murder was discovered, Woyzeck was sent in prison.

Because of the presumably compromised mental state Woyzeck held, for the first time in German history, the concept of insanity was raised by the defense team. The court prompted a doctor, Johann Christian August Clarus, to evaluate Woyzeck’s “periodic madness” to determine whether he had the will to commit the crime. However, the examination didn’t favor Woyzeck, as Dr. Clarus noted, “His physical as well as mental state of mind do not provide any grounds for assuming state of ill health that would diminish his free will and his senses of responsibility.”

Woyzeck was sentenced to death. Although the defense team motioned to object, which led to a second trial on October 1823, the court didn’t reverse the sentence. On August 27, 1824, Woyzeck’s life came to the tragic conclusion when he was beheaded in Leipzig.

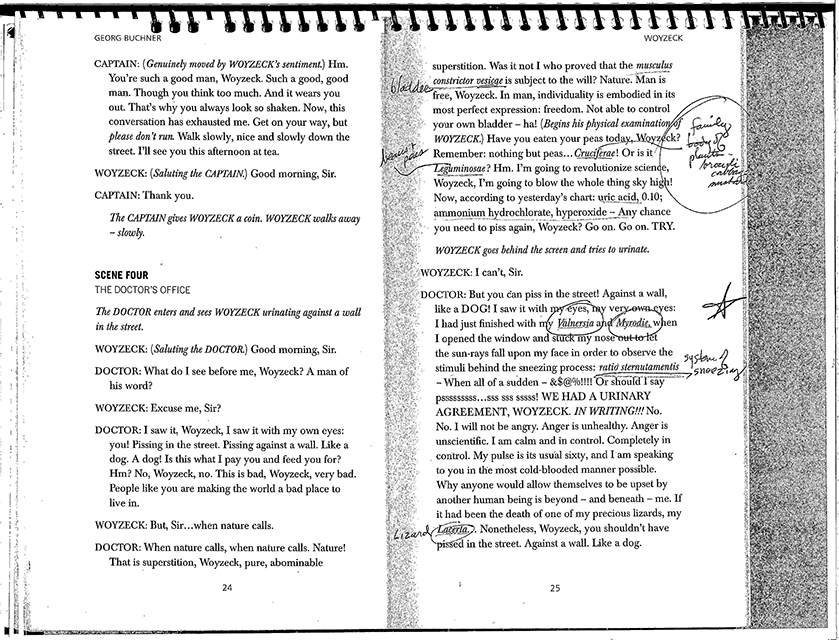

The dramatization of Woyzeck elevated this notable murder case to a stronger display of the madness. In the original script by Büchner, Woyzeck, now the more erratic main character, constantly heard voices of repeated words in his head and was easily agitated. He let a doctor experiment on him, eating nothing but peas to earn a few coins. His affairs with Marie, the fictional female character, led to an illegitimate child. He peed in the streets, had barely any people to listen to him, and was treated as if he was no more than a monkey from a circus. At the culmination of the events, Woyzeck took Marie near a pond, where he mercilessly killed her. After the murder, he returned to a gathering to dance, where the blood on his wrist was discovered. In the end, Woyzeck ran back to the pond, where he was speculated to commit suicide.

Büchner carved out a philosophical discussion about science, religion, power, military, sex, and of course, human mentality, from his depictions. The play fabricated a restless, chaotic environment. Within this compound of disorganized intentions, emotions, and actions, however, Büchner drew a dreadful notion of meaninglessness, that the nature of life was but insignificance. As indicated by the editor notes from Dale McFadden, Professor of Theatre, Drama, and Contemporary Dance, Associate Chair, and Director of Undergraduate Studies at Indiana University, “…I think that Buchner is trying to present a world in which irrational forces must be seen and recognized by all of us, even when it is not in our power to know why they exist. I think his strong interest in Nature and the processes of living and dying drew him to creating a world view where seeing was more important than explaining. Explaining can ruin seeing…”

Daniel Kramer’s adaptation of the play condensed the 29 scenes from the original script to 20, eliminating some characters and dialogues and combining some other. He also added (or paraphrased) some counters between the characters to further develop the sense of chaos from Büchner’s manuscripts.

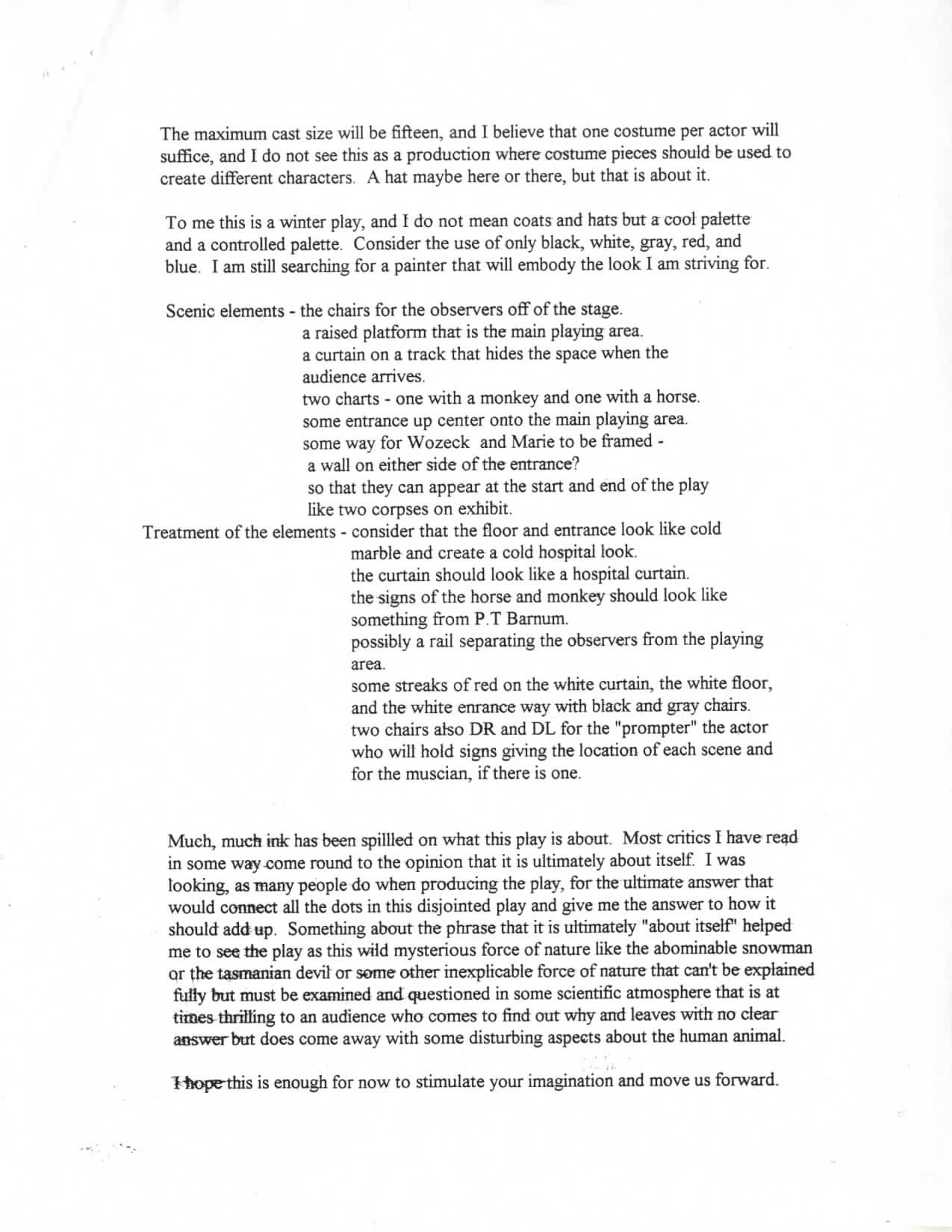

Indiana University’s production of Woyzeck followed this perception to the stage design. There was a strong hint of expressionism regarding the scenic respects of the production, simplifying the setting to a couple of observable benches, a giant wall, some charts to represent the monkey and the horse from the circus. Contrast was also emphasized. Although the color scheme of the design was limited to the yellow to the earth-tone ranges, there would be colder-colored lighting, such as green and blue. The intensity of illumination also employed concentration on certain playing areas, leaving everywhere else (or behind) dim or dark. Finally, contrasting the scenic display all, the actors’ costumes were more sophisticated, clearly tipping the balance of the demonstration of the content towards the characters’ vocal and physical movements.

A senseless, cold delivery to the viewers was intended. If the viewers were to place themselves in this specific scenario, they might get a creepy or even disturbing feeling. It was a world where everything was dangling on the surface, and nothing could matter, even the existence and the existence. The unfolding of Woyzeck’s pain and Büchner’s masterpiece was no short of a chilling, breathtaking experience. When Woyzeck drowned himself, and the light snapped to black, we, the witnesses, in the end, could do nothing but send out a sigh, maybe a numb exclamation:

“What a murder. A good, genuine, beautiful murder.”

______________________

The Marriage Course: IU Opens New Doors for Students by Sabrina Siew & Maddie Stacey

According to Relationships in America, Americans on average have sex 118 times per year. In the past, these sexually active Americans have had very little access to sex education. Thankfully, sex education curriculum in America has dramatically increased in recent years due to the influx of research on topics ranging from STDs, to sexuality, to sexual pleasure. One of the most important researchers who revolutionized how we regard sex and marriage today was Alfred Kinsey, founder and creator of the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University.

As of today, the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction is an essential component of Indiana University and a pinnacle for sexual research. Hundreds of discoveries were made in regards to sexuality, love, and the science behind sex. At the time of its founding, however, these discoveries and ideas produced by Alfred Kinsey were not popular or well-received by the public. Reflecting back on Dr. Kinsey’s work in the mid-20th-century, we can conclude that Alfred Kinsey was a catalyst at Indiana University for progressive thinking. Not only was Kinsey allowing the students here to access information that was not readily available to them, but he was creating an open conversation about sex and marriage in general.

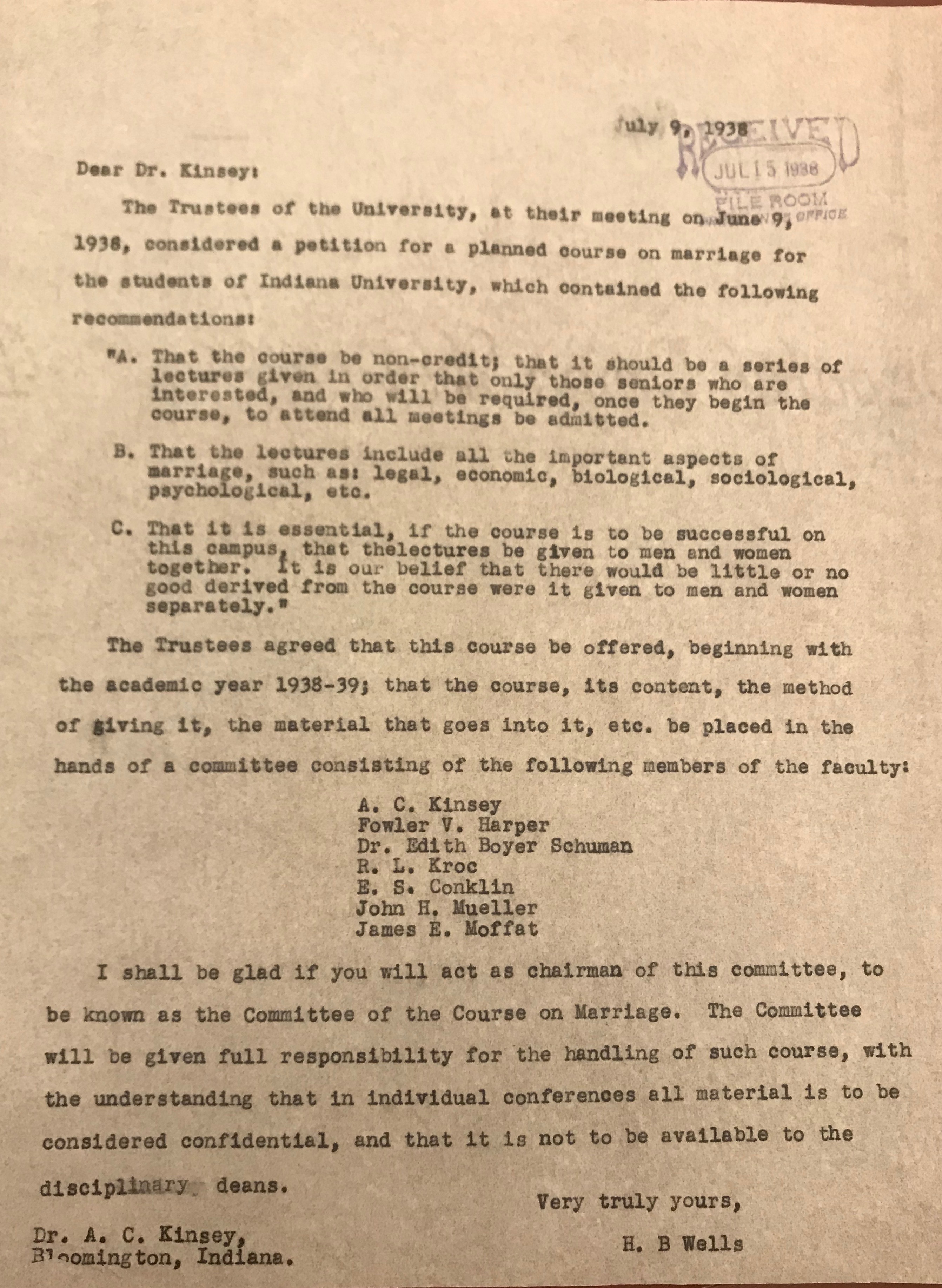

Almost 80 years ago, Alfred Kinsey developed the concept for a Marriage Course to educate young adults on important aspects of marriage. This course covered everything from biology, economics, ethics, law, psychology, and sociology, to even venereal disease. This was revolutionary. Very few available courses or universities in the past had attempted to provide education about marriage in such a comprehensive way. Not only was Dr. Kinsey planning on teaching about the partnership aspects of marriage, but also about sex. Comprehensive sex education by itself at that time would have been unthought of, but integrating it into a course about marriage was just as rare. At the time, Herman B Wells was the president of Indiana University and was an avid proponent of the implementation of the Marriage Course. In correspondence with Dr. Kinsey, President Wells appeared to be not only supportive, but also extremely interested in the results of the course. After working through the concept, and getting IU faculty on board, Kinsey and his fellow lecturers were finally able to implement the Marriage Course into the Indiana University curriculum.

In the summer of 1938, Indiana University welcomed its first class of students enrolled in the Marriage Course. This course was available to only upperclassmen and married students with the goal of educating these young adults on the truth about marriage. Guest lecturers were brought into the classroom to teach students about marriage from both their own perspectives and their knowledge from their individual fields of study. Though the course was not offered for credit, it still received a large number of enrollments, totaling 98 students in its inaugural class, and flying to over 200 in the next semester. The initial course consisted of 14 lectures, from various IU faculty, covering distinct aspects of marriage. Surprisingly, or perhaps unsurprisingly, an overwhelming majority of the initial participants wanted more information about the biological aspects of marriage following the conclusion of the course.

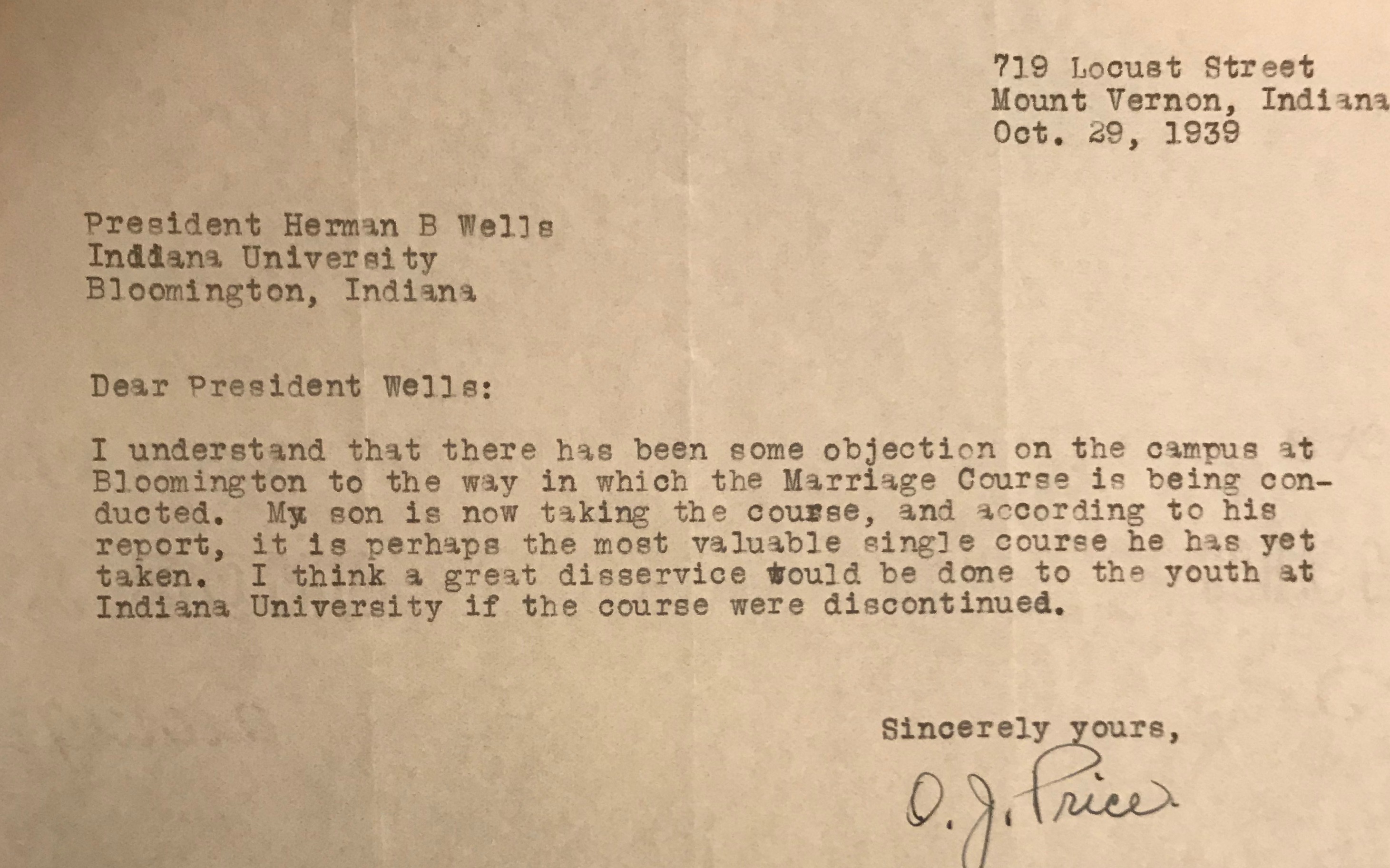

Although the Marriage Course was incredibly popular within the student population, concerned parents and members of the community were worried about the teachings of such a taboo subject. Even faculty members were in shock at some of the teachings, and they had no problem voicing their concerns. Though the idea of marriage was common, the thought of any real sex education in a university capacity was frightening and even threatening to many people’s ways of life. An influx of letters regarding the removal of this course started to flood the offices of Indiana University. Dr. Kinsey and Herman B Wells were prepared for this backlash. What was surprising was the equal amount of letters that flooded the office with voices of support for the new course.

Parents were writing in support of their children, reminding Dr. Kinsey, Herman B Wells, and the Board of Trustees that this course was an important part of learning for the young adults at Indiana University. They believed that learning about all aspects of marriage was a vital part of education, and it would be an injustice to take that away. The letters of support for the Marriage Course are evidential proof that with the help from Herman B Wells, Dr. Kinsey was changing the course of history at Indiana University and welcoming our school into a more progressive age.

After this huge influx of praise and criticism, the board came to a decision on the Marriage Course. Unfortunately, Dr. Kinsey was presented with an ultimatum: either move the course to the Medical Center and completely change the curriculum or sever his connection with the course and present lectures independently if he wanted to continue teaching the biological aspects of marriage. In response, Dr. Kinsey made the decision to remove himself as the chairman of the course.

Even though President Wells offered Dr. Kinsey the opportunity of lecturing in the new Marriage Course, Kinsey denied the proposition. He wanted to continue his research in human sex behavior free of reproach while students continued to receive the education they needed regarding the road to a healthy marriage. From his correspondence with President Wells, it is clear that he felt it would be too difficult to conduct the course he created without providing the sex education he believed Indiana University students deserved.

Although Dr. Kinsey was stepping down from his chairmanship, he did not plan on leaving the Marriage Course in incapable hands. Instead, Dr. Kinsey worked diligently with President Wells before leaving to ensure the faculty overseeing the course would justly cover all aspects of marriage, just as Dr. Kinsey intended in the outset of the course.

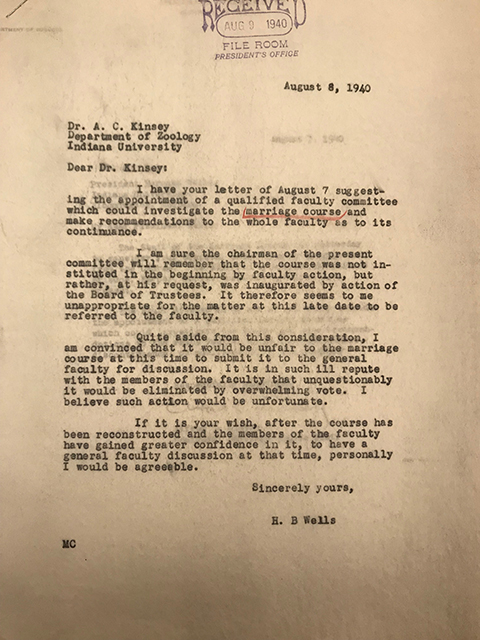

Kinsey created the idea to have a faculty committee investigate the course and develop the best course of action regarding the retention of the course in Indiana University’s curriculum. President Wells feared that doing so would result in the elimination of the course as a whole, and subsequently denied Kinsey’s request. However, with much hard work on both Kinsey’s and Wells’s part, they were able to find a new chairman and a few new faculty members to teach the curriculum.

Fortunately, the course survived all the upheaval and continued successfully at Indiana University for several more years, before its conclusion in 1943. Though there was restructuring and variation in the lecturers and content, the overall heart of the course remained the same, even without Kinsey’s influence. Although a time period of five years for a course may seem too short to be impactful, the fact that the Marriage Course existed in any real capacity during the mid-20th-century is unbelievable. The amount of discussion it initiated inside and outside the classroom was and still is inspiring. In our current day and age, it seems so simple to learn about sex or recognize the aspects of a successful marriage. But much of that would not be possible without the help of progressive thinkers like Alfred Kinsey who fought for our right to knowledge.Thanks to Alfred Kinsey, the Marriage Course opened doors that Indiana University students may have never had the chance to enter into before.

Leave a Reply